A Clockwork Orange

This week's Viewer film essay: on Stanley Kubrick’s A Classic Orange. What kinds of writing would you like to see from the Viewer? All suggestions much appreciated. Let us know at editors@theviewer.is

Spoilers Ahead (and for Taxi Driver, Parasite, and Barry Lyndon), and ultraviolence throughout.

Here is a typical character arc: the main character has a problem. They are living life in a self-perpetuating stasis, in need of change. An inciting event comes along to break that stasis, and they are forced to undergo a journey that spits them out as a better person.

This is a truncated version of Joseph Campbell’s cherished Monomyth, and most stories follow it in some way or other. I’ll call it the Change arc. Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” follows a much less common pattern: the Repetition arc.

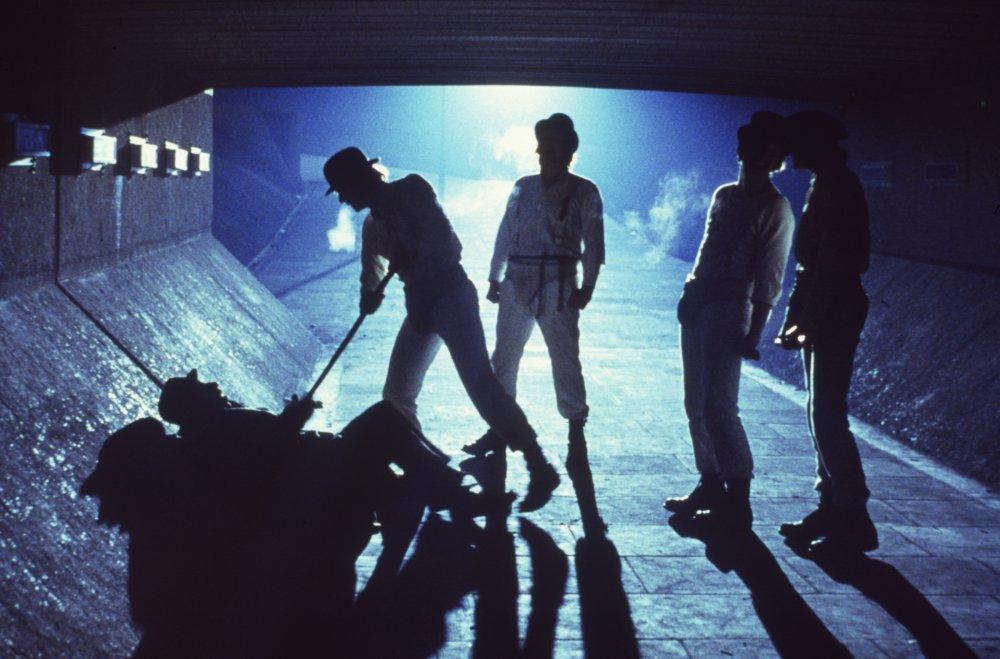

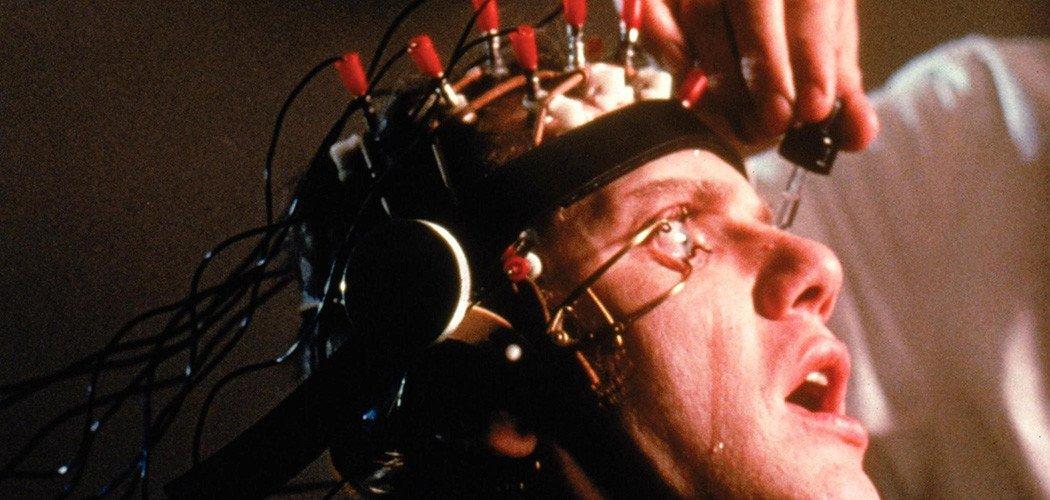

The first two stages of the Repetition arc are identical to the Change arc. The hero of “A Clockwork Orange,” Alex DeLarge, is a young hooligan who wanders a futuristic Britain with his street gang the “droogs”, raping, assaulting and defacing everyone and everything that comes in their path. Here we certainly are presented with a problematic, self-perpetuating stasis. One night, during a break-in, Alex is arrested – our inciting event. Over the next few years in prison, he is institutionalized and put through an experimental indoctrination program known as the Ludovico technique, all in a bid to rehabilitate him. This portion of the film serves as his journey, his struggle to become better.

The treatment initially seems to work – it conditions Alex’s mind to react negatively to sex and violence. He is released back onto the streets. And yet the film doesn’t end with Alex having changed or become a better person – in the last scene, he finds he has lost his aversion to sex and violence and begins once again to experience vulgar sexual fantasies. “I was cured, all right!” he quips. He has returned to his first act stasis; after all his narrative trials and tribulations, nothing has really changed.

The Repetition arc has been used in many great films. “Taxi Driver” is the story of a disturbed loner who struggles to become better, ending up showered in public praise but just as disturbed as he always was. Bong Joon Ho’s recent critical darling “Parasite” is about a family that strives to be rich and never succeeds; a socio-economic twist on the Repetition arc. Kubrick himself would return to it with the underrated “Barry Lyndon,” the tale of an Irish rogue who tries to deceive his way into a fortune, but ends up alone, crippled and destitute, all of his ambitions having disintegrated.

The Repetition arc is essentially a pessimistic one. It tells the audience that things never change, that people live in hopeless cycles predetermined by their own characters and that their struggles to achieve moral betterment or success will inevitably collapse in on themselves. One might think that the Repetition arc would be narratively unsatisfying, because it fails to transport the audience. They don’t learn anything from the story. This isn’t the only kind of storytelling technique, though. If done right, symmetry and repetition can be just as narratively cathartic as growth. There is a powerful unity to a story that is bookended by identical scenes and sentiments, a sense of overarching stasis that is almost comforting in its nihilism.

We know that the Repetition arc is important to Stanley Kubrick’s film, because in the book upon which it is based, Alex does change. Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel ends with Alex growing discontent with the criminal life and becoming a productive and happy member of society. Surprisingly, his original story is the Change arc incarnate. American publishers insisted on cutting the final chapter so the novel would end on a darker note, lopping off the Change and replacing it with Repetition. Burgess reluctantly agreed, although he called the American version “badly flawed.” When he was adapting the book for the screen, Kubrick opted for the American ending, going so far as to say that he never even considered including that final, redemptive chapter.

What does the Repetition arc signify in the story of “A Clockwork Orange”?

Well, both the Repetition and the Change arc start with a problem that the protagonist faces. Alex’s problem is that he is a bad person. He’s bad not because he is misguided, or depressed, or self-centered, or angry, or pretentious, or lazy – he’s simply evil. Burgess, Kubrick and McDowell crafted an amoral man, a man whose entire life is built around delighting in the pain of others. Early in the film, Alex and his droogs pass a homeless man who begs them for money. Cackling, they mercilessly beat him unconscious with their batons.

The first act of the movie is almost entirely devoted to showing how bad Alex is. One might assume that Kubrick is trying, with these horrific scenes, to distance the audience from Alex, to cut off any possible empathy we might feel for him – but Kubrick said, “Alex symbolizes man in his natural state, the way he would be if society did not impose its ‘civilizing’ processes upon him. What we respond to subconsciously is Alex’s guiltless sense of freedom to kill and rape, and to be our savage natural selves, and it is in this glimpse of the true nature of man that the power of the story derives.” Kubrick wants us to experience Alex’s actions as evil, yes, but also as free – there is a kind of wild, barbaric joy in his ability to act badly and remain unpunished.

This freedom makes Alex’s eventual arrest and his tortuous imprisonment feel unbearably oppressive. The brand of re-education that he is subjected to is inherently futile – from the government’s perspective, it is a process of rehabilitating and morally improving a delinquent member of society. From our perspective, it is the equivalent of chaining a grizzly bear to a seat and trying to teach it advanced calculus. Although the “Ludovico technique” may subdue and sterilize Alex’s savage character, it can never make him good. Socrates emphasized in several Platonic dialogues that you cannot force someone else to have knowledge. Virtue is an intentional, personal state of the soul. The government has two choices; restrict Alex’s freedom, in which case he is little more than a robot, or let him exercise it, in which case he will leave a trail of destruction and cruelty in his wake.

The “journey” towards goodness that Alex experiences is a regression, rather than a progression. Thus, the second act of the Repetition arc is not the same as the second act of a Change arc – this journey is pointless from its inception. The Repetition arc mitigates the shock of its seemingly unresolved ending because the journey that fails to succeed was doomed from the very start. It is also important that Alex’s journey is not voluntary – it is quite literally forced upon him (a fact which is shockingly visualized in the infamous Ludovico scene). In this way, “A Clockwork Orange” is a variation on the traditional Repetition arc, replacing a failed personal struggle with a failed attempt at outward rehabilitation. It says that our personal efforts at development may be doomed, but prisons and indoctrination programs are no better.

Perhaps, then, the point of the Repetition arc in “A Clockwork Orange” is as simple as this; a bad man cannot be made good. Alex has a problem, a problem that is unacceptable in its natural state – for the writer whom Alex and his droogs cripple, or the writer's wife, whom they gang-rape, or the cat-lady Alex bludgeons in her own home – yet the Ludovico technique is just as hopeless. Alex’s rotten soul sits festering at the ideological center of the film, like a tumor for which scientists have no cure. Kubrick eschews Burgess’s more positive outlook, sending a message about human nature so cynical that the Repetition arc is the only acceptable mode of expression.

Back to that enigmatic ending. Alex sits in a hospital bed. The adoring press crowd around, snapping photos of him. The media is choosing to portray him as a victim of terrible state oppression – as we explore his sick imagination in those final moments, we recognize that this “victim” is not so innocent and never has been. The one thing that could have changed Alex would be a genuine attempt on his part to improve his soul, but from that opening shot of Alex staring malignantly into the camera, we know that he doesn’t have that in him. From the crooked timber of humanity, nothing can be made straight.