Jon Ingold on translating archeology into video games

Every week at the Browser we conduct edifying interviews with interesting figures. Today we speak to Jon Ingold, game designer and founder of Inkle Studios — developers of interactive fiction games that have won BAFTA and Independent Games Awards accolades. Here Ingold discusses translating the practice of archeology into a video game, designing branching narratives, and classic text adventure games.

For more interviews, see the rest of our Browser Interviews.

Linda Yu: Could I ask you start by discussing Inkle and some of your projects?

Jon Ingold: Inkle is an independent developer of narrative games; founded by myself and my friend Joseph Humfrey pretty much exactly 10 years ago (Nov 2011). Our original idea was to take what we'd learn in the games industry and apply it to mobile devices and book publishing, to try and make interactive stories for the mainstream, book-reading market — games in disguise.

After awhile, we found that book readers generally liked books and distrusted games, and game players mostly weren't interested in books, so then we went the other way, and started making games which were suspiciously book-like, and this went a lot better.

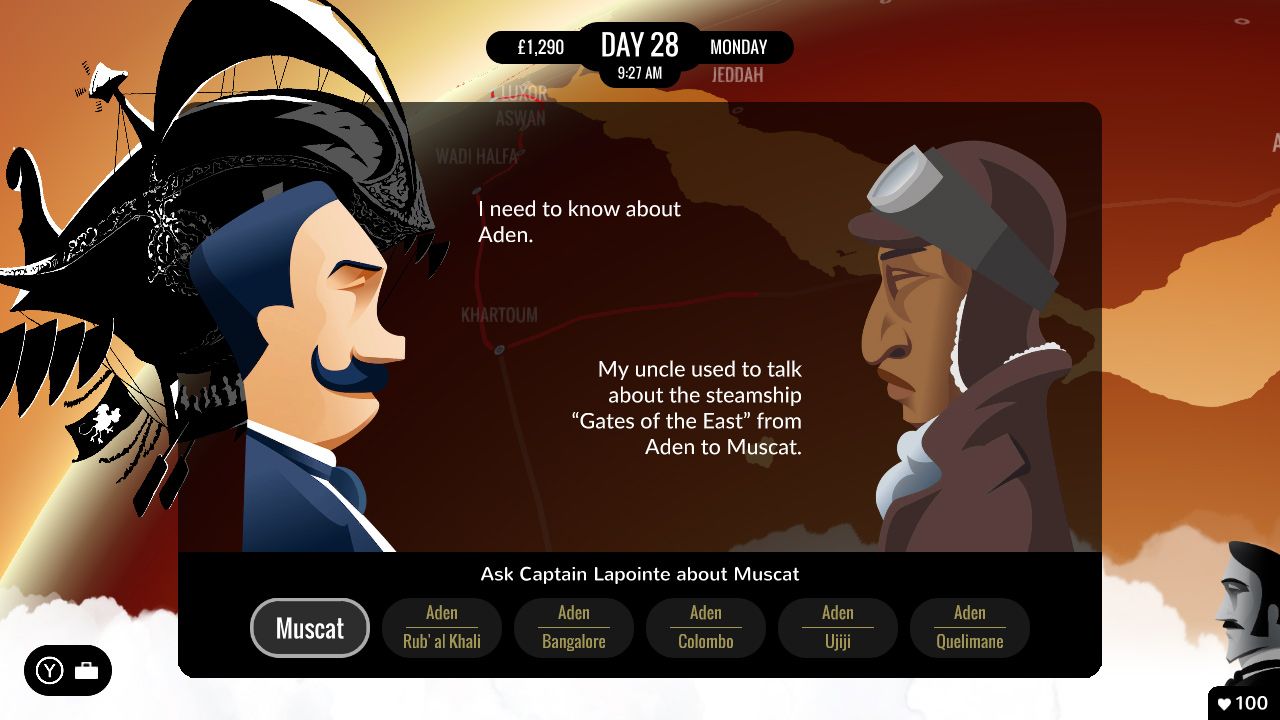

Our first breakout hit was Sorcery!, an adaptation of an old gamebook title into a slick, responsive, adventure across a fantasy world. Then in 2014 we released 80 Days, an interactive retelling of Jules Verne's novel, and that gained quite a lot of publicity and success — including in the book world.

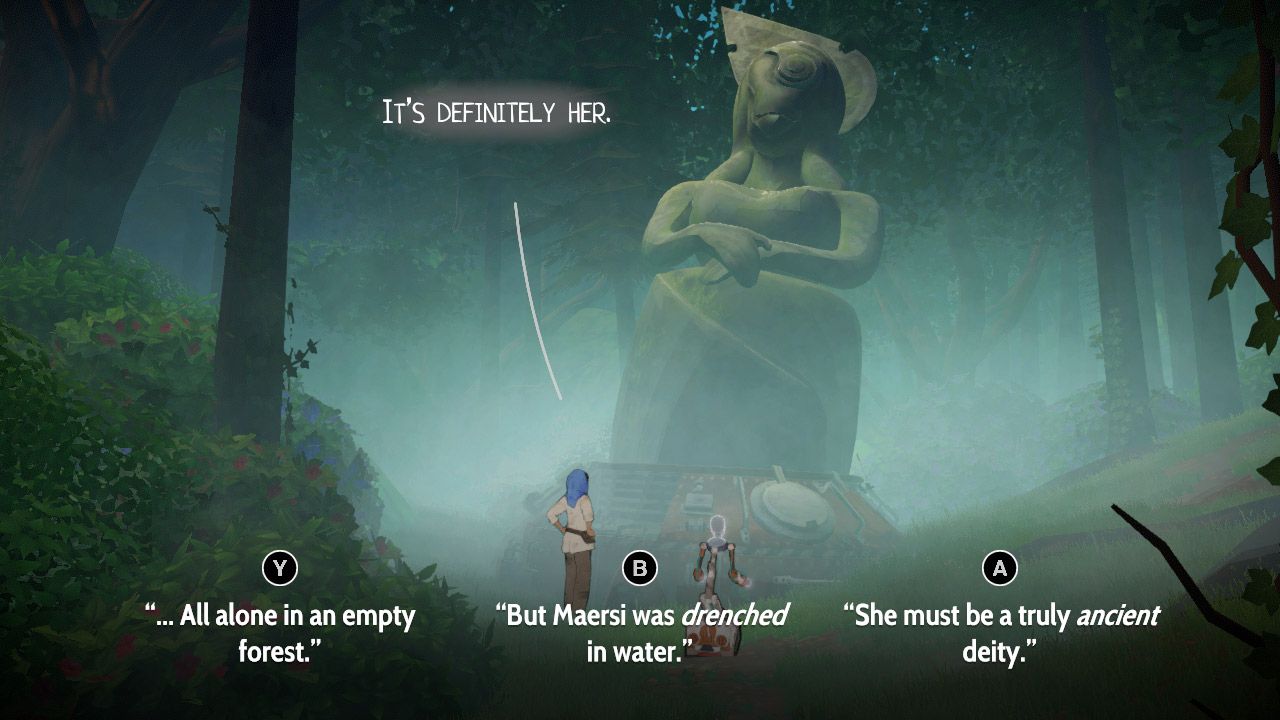

Since then we've made a 3D adventure around translating a hieroglyphic language, which is very popular with archaeologists; a strategy game based on the legends of King Arthur; and a reverse-murder-mystery where you're the one whodunnit.

We write all our games using ink, a scripting language for interactive fiction we developed that allows for fast writing, redrafting and testing of interactive stories - we open-sourced it in 2016 and it's used by other studios all around the world.

Linda Yu: I didn't realise you were targeting a book-reading audience at one point, would you ever publish a book as well? A reverse of what you did with Sorcery?

Jon Ingold: We actually are doing that right now! We've been working on a novelisation of Heaven's Vault, and it's just about ready to be published. We're doing a limited print run at the moment ourselves, but hoping to explore real publication too.

Translating the practice of archeology into a video game

Linda Yu: Speaking of which, could we talk a little more about Heaven's Vault, your hieroglyphic language game? It was originally recommended to me as "surprisingly accurate to the actual process of solving a language" and "about space robots".

Jon Ingold: So, we'd just finished 80 Days, and were looking for a biggish project to try and push our interactive storytelling ideas further. We wanted something that wasn't episodic, with a full arc from start to finish, but where the player could follow up whatever leads they were interested in, and where they would never get stuck and need to backtrack.

We were a bit stuck on a theme or setting for a long time, however, everything felt rather uninspiring, until I woke up one day with "SPACE ARCHAEOLOGY" in my head. It brought together a few things we were interested in - science fiction and settings with lots to discover and explore and learn - and a focus on people, not machines, or guns, or military operations, or puzzles involving sliding blocks around.

We took a long time trying to think of things an archaeologist might actually do in a game. Repairing broken pots isn't very interesting (sorry, archaeologists!) and while exploring is good, it's quite a passive thing: games do better when the player has something active to engage with (hence "walking simulator" being considered a negative term).

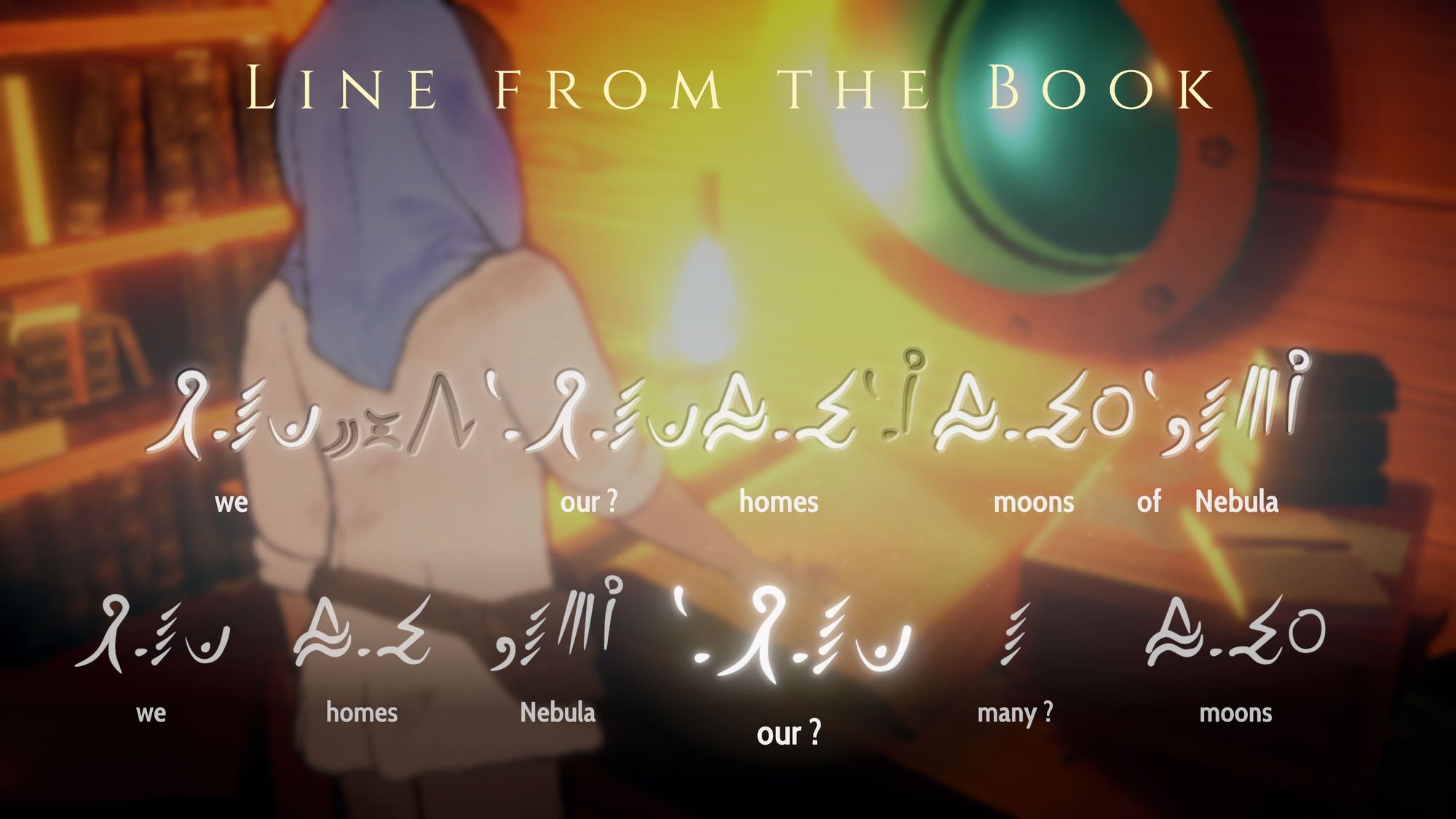

Then we had the idea of translating a language — and in particular, the idea of finding inscriptions, trying to decipher them, and having your reading of them inform the characters understanding of the world. That really excited us, because it meant we could tie together the gameplay activity with the narrative, directly, and coherently. It was also a real head-scratcher — how does one make an engaging translation experience? But that kind of challenge is quite interesting.

From there we were just developing out the mechanics and the world of the game, which in turn drew from a lot of different sources.

Linda Yu: In relation to drawing from sources, when I preparing for this interview a friend mentioned that you're the son of the archeologist Tim Ingold — whose essay Materials Against Materiality I once recommended on our site. It was interesting to me how in some ways — especially relating to the question of how entirely different creatures or cultures would interpret the same artefacts — your game is somewhat of a textual response to that.

I was wondering if you could discuss a little what sorts of texts you drew upon when putting together the world in the game.

Jon Ingold: My father is indeed my father, and I was brought up in a household full of a rolling supply of anthropologists and archaeologists, bringing with them stories of cultures from all around the world, along with the academic perspective on those cultures — much more about reaching for an understanding of the human being below the culture than the excitement of the differences between that culture and ours that you get from journalistic representations of other people.

That was really formative: I wanted to create a world in which the player knew nothing (but could learn) but understood everything (but find that understanding changed the more they learned). So for instance, they have a religion on Iox - it's not any of our religions, but it's very easy to understand how it works, and how it affects people, because religion is quite a common thing amongst human beings and despite differences in what it says, it's pretty consistent in how it says it.

Designing a logical science fiction setting

Jon Ingold: I was also really keen on it being a "good" science fiction setting. These are rare! Sci-fi often just throws stuff at the wall whenever it feels like, leading to universes like the Star Trek one, where — due to thousands of inventive and creative episodes, they can now solve almost any problem by simply teleporting things around, and they also have basically unlimited time travel and telepathy too.

I looked at the work of Ursula le Guin and Gene Wolfe, two of my favourite writers. Their worlds are deeply, deeply logical; underpinned by a few inventions, or a few ideas, with the stories and the characters existing on the surface of the work that results from those assumptions.

Linda Yu: Ah yes, what I thought was novel about Heaven's Vault was how you managed to create that feeling of being prevented by a limited worldview from interpreting a primary text written with a completely different set of information.

Many science fiction books and games can have full volumes of lore, but it doesn't meaningfully change the behaviour of the player or characters.

Jon Ingold: Yeah, I'm very sceptical of lore for lore's sake; it's just stuff someone made up. What's interesting is connections between things. So two bits of lore that are actually the same once you understand where they come from, that's interesting. (We do that a lot in Heaven's Vault.)

What should be the purpose of archeology?

Jon Ingold: For the archaeology, I was stuck for a while — originally I was thinking about classic archaeological tropes — Indiana Jones, Agatha Christie's archaeological stories. But it also seemed deeply weird: archaeology as a hobby/sport for rich people, and a destructive one too; rather like rhino shooting.

Then one day I googled "interesting archaeologists" and came across the work of Dr. Monica Hanna, an Egyptian Egyptologist who has worked on the looting of Egyptian artefacts by Egyptian people and the questions of who owns Ancient Egypt — and that was really, really inspiring. Archaeology as a way of touring the past like it was a zoo doesn't work for stories (it has no consequences) but it's also deeply othering. Archaeology as a way for a culture to look at its own position in the world — how did it get where it is now? Who benefits from what was left behind? That was something I could work with.

Linda Yu: That part about archeology's place in the world is really excellent, I often think the way we are taught about our past history is as a series of untethered facts about events that are "finished" and how much of politics is just the expression that there's no such thing.

Branching game narratives versus a linear ones

Linda Yu: As a game designer unlike an author, you also have to consider the behaviour of the player. Does that change how you approach telling the story you want to convey?

Jon Ingold: I don't see interactivity as that big a deal, which is not to say I don't think about it all the time, but when you're writing any kind of story, you set up a world — characters, motivations, technology, power structures, whatever — slightly independently of the protagonist. The protagonist moves through the story taking the best decisions they can, and the world constrains them to make interesting things happen. If the protagonist ever gets stuck or gives up, or just "wins", the story falls over, so you have to balance the routes in the story world and what the the protagonist is able and willing to do to keep the ball rolling along.

That's true regardless of medium! When I'm writing "linear" fiction I usually have a few different ideas for what the character could do or say next; in the interactive medium I write all of them; and in the static medium I choose the one I think works best. So writing interactively is much slower — you have to go broad, all the time - but it's also less stressful; you don't have to pick the very best option all the time - and if the protagonists decisions don't always make sense, that's the players fault and not yours!

So you're sacrificing perfection of story for breadth of possibility. But the overall story — what's to be discovered, and why, and roughly speaking how — is a level up from what the protagonist does; it's encoded into the shape of the world. And if that works, it should work in either medium

(I know this from experience now having turned Heaven's Vault into a novel!)

This does mean I reject certain kinds of interactive storytelling - I'm not interested in the player having "control", in them getting to choose what kind of story they have; or say, being able to date anyone — that all feels deeply wrong to me. A player should be with the protagonist, not be the protagonist, and a protagonist should always be a bit at sea, or there's no story

Getting players to engage with morally ambiguous characters

Linda Yu: The idea of the player being with the protagonist reminds of your most recent game Overboard! where you play as a murderess trying to cover up her tracks. As a video game player I'm slightly cautious of confrontation — definitely a person who keeps every health potion — so at one point there was a character I struggled to frame because she would burst into a fountain of tears every time I tried to speak to her. Do you think of ways to make players follow options and routes they might originally not consider due to their own preferences/instincts?

Jon Ingold: It's definitely always a balancing act.

In a film, you might have a character who's very morally ambiguous, and some viewers will be fine with that but others might find it really difficult to identify with them. As a writer you try to get out ahead of that, by making sure there are enough rewards to be invested — make the character attractive to be around, funny, smart, or make them get their comeuppance in a really satisfying way.

Interactively, the player has to make more effort to be with that character and in that story — they really have to show up, and if things become a slow or get a bit too much, the player may well quit out. But the tools and techniques are largely the same. In Overboard, we make some promises to you — Veronica will never been too scared; she will never be injured, trapped or hurt; she'll always have a ready quip and another idea; she'll never feel too much remorse. So engaging with her — into confrontation, or murder — always feels like a "safe" thing to do, and hopefully a transgressive, enjoyable thing too. But I'm sure there are players who just despise her so much they can't play; and that's fair enough.

So like any story we try to lure people into getting invested, by hook or by crook; interactivity gives us a few more hooks.

Linda Yu: Her cheerful remorselessness even when caught was quite fun.

Jon Ingold: Ideally, it should be like being dragged into a scrape by your much-braver-than-you friend.

The narrative engine ink

Linda Yu: To scroll to Inkle, since you've released your narrative engine to the public have there been any projects made in ink that you think people who enjoy your own games might be interested in?

Jon Ingold: So my favourite made-in-ink game is Over the Alps, but that's because I co-wrote it.

One thing that's great about ink is we get a real variety of projects made in it. So Signs of the Sojourner was written in ink, and is very good; so was Neocab, which is more like a classic Visual Novel; Failbetter's upcoming Mask of the Rose is ink; but also the recently-released cell-shaded gliding game Sable.

But there aren't many games that really fit our style exactly of writing and storytelling — people use ink their own way.

One of the reasons we released it was because we found that ink allowed us to actually write — not code dialogue, or assemble it, or design it, but write fluently. And I felt that the one thing holding games writing back from being brilliant wasn't the humans at the keyboard — they're perfectly talented — but the interface they were allowed. Ink tries to let writers just write, and be flexible as they do it. I hope it's having an impact.

Classic text and modern adventure games

Linda Yu: From that list, it does seem that you've been been somewhat successful in that regard. In turn, what were the games that got you interested in making text games? I remember playing Bronze or Galatea as a kid, but I suppose those are the obvious grand dames of interactive games.

Jon Ingold: Firstly, I suspect I'm a little older than you — when Galatea came out I was part of the interactive fiction community that Emily was writing in, and writing my own games, and we were both responding to previous games we'd played.

My first text games were the Infocom classics — The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Sorcerer. I enjoyed them, but the one that really excited me was called The Witness; it was a detective game with a tiny cast, but you genuinely could solve the crime through finding evidence, having ideas, putting the facts together, and having a resolution.

It didn't feel like a game — it felt like a [clumsy] theatrical experience. I tried their other, more complicated detective games — Deadline, Suspect — but they were too complicated; it was too hard to follow what was going on, or what you were meant to be doing.

Then I discovered the Inform community and started writing my own, and there were lots of games made by that group that were transgressive, exciting, creative, and inspirational: too many to list all the ones I liked (and a lot I can't remember now! But they went in.) Emily Short is very well-recognised from that time, but at the time the bigger names were Andrew Plotkin and Adam Cadre.

Cadre in particular really changed the idea of interactive fiction forever, I think. (Other people would have done it, I'm sure, but I believe he got there first.)

Linda Yu: Hate to confess, I foolishly thought I was scraping the origins of the genre by remembering MUD.

Jon Ingold: Aaron Reed's been doing an amazing blog series called "50 years of text games" that starts with 1979 or something ridiculous, but it's fascinating

Linda Yu: It's interesting that you describe those games as puzzles, because what always struck me was how your games are normally described as narrative experiences — like Gone Home or Edith Finch — but to me they are always wrapped around a central puzzle or game mechanic to solve that keeps people reading.

Jon Ingold: It's just storytelling to me. You can't tell a story without some kind of central mystery, or hook; and without something for the audience to be thinking about as they go along. Some games ship on the audience thinking about how pretty the game looks; or how great the action is; and the central mystery is sometimes "how long is this game and can I finish it"... but for me, I get bored very easily, so I'd rather have something I can really chew over.

So I want things to do in the story that aren't pointless and repetitive; I want consequences to think about; I want characters who seem like real people; and I want a story with places to go.

I wouldn't describe it is a puzzle exactly - there isn't a "right answer" in Heaven's Vault, for instance, and even Overboard is way more open than a puzzle label makes it sound... but there are things to do, and they have consequences, and you can strategise and plan and reason about the game and your actions within it, and that's what makes the world come alive.

Linda Yu: That is a very illuminating perspective.

I just noticed that the time has flown by so, finally, are there any upcoming projects we should look forward to?

Jon Ingold: We're currently developing a game about the Scottish Highlands but there's no release date lined up for that yet. Otherwise, we have the novel coming out soon, and after that - who knows?

Linda Yu: Thank you so much for your time and your incredible insight.

Jon Ingold: Thank you! it's been a pleasure.

Related Links

Jon Ingold on Twitter

Joseph Humfrey - co-founder of Inkel

Inkle Studios, the ink scripting language, and their games:

- Sorcery!

- 80 Days

- Heaven's Vault - novelisation of Heaven's Vault

- Pendragon

- Untitled game about the Scottish Highlands

Materials Against Materiality recommended on The Browser

Egyptian Egyptologist Dr. Monica Hanna

Agatha Christie's archaeological stories

Games written in Ink:

Classic Interactive Fiction Games:

Aaron Reed's "50 years of text games"

Major interactive fiction names: Emily Short, Andrew Plotkin, and Adam Cadre.

This interview was conducted over instant messenger and has been lightly edited.

Looking to hear more from interesting people? See our other Browser Interviews which include conversations with QNTM on anti-memes and other secret knowledge, A Literal Banana on the problems with social science, and Chris Williamson on having an existential crisis while being on Love Island.

Elsewhere on the Browser, see: The Reader, our daily commonplace book of clippings and quotations; Notes, our occasional blog; Academia, our Browser formula applied to research papers.

Not yet a subscriber? Every day, The Browser Newsletter sends you five fascinating pieces of writing to surprise and delight you, each one hand-picked and beautifully capsuled by our editors Caroline Crampton and Robert Cottrell. In a world consumed by bots, noise and breaking-news, The Browser gives you carefully-curated writing of lasting value.

Get our recommendations for the five best articles every day: