Death In Davos : Day One

By "Emily Adjarian"

Author's note: This serial is a work of fiction. The people and events described in it spring directly from the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actually existing people and events is entirely coincidental.

Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six | Day Seven

Speculate and debate on Discord here.

Saturday 13th January 2024 — Zurich to Davos

IN THIS EPISODE: A train from Zurich to Davos — An inconvenient Frenchman — An accident with coffee — A disingenuous billionaire — A deadline in Ukraine — A dubious proposition — A gruesome death

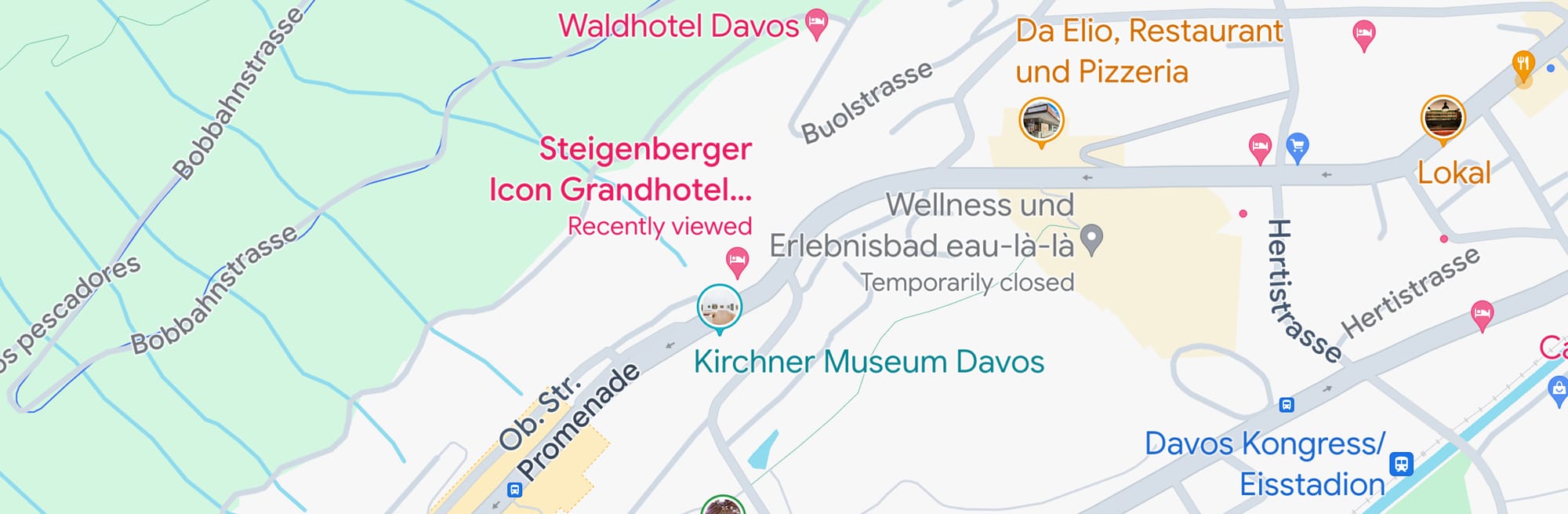

SOMETIMES IT IS better to travel hopefully than to arrive, thought Olena, as she boarded her train in Zurich Hauptbahnhof. Whatever seasonal specials they might have on the menu when she got to the Steinberger Grand Hotel Belvedere in Davos, the staple item in her diet this coming week was going to be a well-honed investment pitch repeated over any number of pre-dawn coffees, second breakfasts, lettuce-leaf lunches, faux-coincidental collisions in hotel lobbies, time-outs from plenary sessions, novelty nibbles at cocktail parties, and night-owl cognacs in the Belvedere Bar. By the end of it all she hoped to have nailed down, one by one, one on one, her potential friends and her potential adversaries. That was the power of The Virtuous Circle.

There would be a few surprises at The Circle, no doubt, and plenty of gossip — some of it even about her. Three years ago she had been a rising star in the office of The Doc, as the Herr Doktor, founder of The Circle, was called by everyone outside his hearing. She knew the Circle inside-out and The Circle knew her.

But this year she was not there to jump when The Doc said jump. She was there as an official participant, the director of Reconstruct Ukraine. The chip embedded in the White Badge on her lanyard was The Circle's equivalent of Access-All-Areas — a passe-partout that would get her inside the rooms inside the rooms inside the rooms.

For The Circle was not simply one circle, but a set of concentric circles, with The Doc at its centre. The outermost circles were for holders of colour-coded badges who were admitted to programmed talks and discussions only, and sometimes not to all of those. They were the session-fodder. Their job was to listen enraptured to the Finnish Minister of Folklore or the CEO of a Liechtenstein Landesbank while not even noticing that the rest of the room was filled with relative nobodies like themselves.

The people who mattered, and who wouldn't generally be listening to the Finnish Minister of Folklore, would tend to be talking privately to one another in their hotel suites, or gathering in other rooms around the Congress Centre in groups of 12-20 for what the staff called "Ringlets", which were by-invitation seminars convened to discuss specific topics of immediate importance to the participants.

This year, for example, big-bank CEOs would discuss whether they should maintain a united front against cryptocurrencies or whether the time had come to start offering cryptocustomer accounts.

The smallest circles had no names at all and usually took the form of breakfasts and dinners to which not even a White Badge alone was enough to ensure access. Attendance to these was reserved for two categories of people, known informally to Circle staff as "predators" and "prey".

Prey were the rare celebrities whose names any Circle member would be proud to drop once they were back in London or New York: "I tell you what Barack said to me last week ..."; "I was having breakfast with Angelina ..."; "I don't usually agree with Greta, but ..."

Predators were Circle members who were (a) presentable on such occasions and (b) only too happy to pay the non-trivial supplement for VIP status.

Olena would be in her element at The Circle, and yet somehow she wasn’t looking forward to it. How could she be? How could anybody claim to enjoy anything when Ukraine was such a bloody mess — when the whole world was such a bloody mess?

She was there to extract promises of support for the post-war reconstruction of Ukraine from some of the richest and most powerful people in the world, people who could do literally anything with their money. They would be nice enough to her, mostly. They would show polite interest, mostly. They would ask intelligent questions, mostly. But all the time, every one of them would be asking themselves the same question: "What's in this for me?"

Olena took her seat in the middle of a first-class carriage, an indulgence by her own modest standards but one that could pass for virtue-signalling among other White Badge holders who typically arrived at The Circle by private plane, helicopter, or chauffeured Mercedes-Benz. Besides, she needed some peace and quiet, calm before the storm.

She placed on the table the two (it was a long journey) cups of coffee which she had bought at a Starbucks on the platform in Zurich, and pulled out her copy of Vladimir Sorokin’s Day Of The Oprichnik, which she wanted to finish before Landquart, the station where she would change for the local train to Davos-Platz. But the carriage was warm and welcoming. Her eyelids were heavy. Would sleep or Sorokin prevail? Sleep, probably, and perchance to dream. Already she was drifting off, lost in thoughts of the days ahead.

Olena had always felt sorry for first-timers at The Circle who arrived thinking that they knew how to network. Anywhere else in the world a person could easily spend their life handing out business cards and scribbling down email addresses while remaining innocent of the power-dynamics which kicked in when you tried to network at scale. At The Circle, the laws of networking operated with almost embarrassing clarity.

The basic law was that Circle members came to network up. A few at the top came to network at their own level, but nobody came to network down. The result, when you put five hundred people in a ballroom, all of whom were trying to capture and escape one another simultaneously, was a spectacle halfway between Brownian motion and ballet.

She had also felt sorry for those first-timers who came to The Circle expecting to be electrified by important people saying challenging things. The Circle was not a place for people who truly wanted to change the world in a good way. The Circle was a handsomely-upholstered comfort zone for people who had already changed the world, not necessarily for the better, and now wanted to cover their tracks.

The Doc's special genius, and the gift which he looked for in his staff, was to create an atmosphere of free-thinking debate while ensuring that everybody understood the limits of that debate and that no White Badge member was ever publicly embarrassed or deeply offended. Argument was allowed, but ad hominem argument was not. You could question somebody's facts, but you could never question their honesty, their motivation, or their importance.

Of course there were aberrations. In 2019 a young Dutch academic had gone off-piste by declaring that if the people in her plenary session did indeed care about the reputation of capitalism and the state of the world, they could best redress both by paying more taxes, or, indeed, in some cases, by paying any meaningful taxes at all.

It was not the banality of the complaint which gave offence so much as the complainant's lack of irony. She would not be invited back.

But nobody is ever thrown out of a Circle session. What happens instead is that a member of the session monitoring team — in this particular case it had been Olena herself — comes to sit down next to the trouble-fête, whispers praise for their "bold" intervention, proposes that they continue the "conversation" when the session is over, and remains sitting next to them for the balance of the session lest they be minded to make any further contributions.

In effect, The Circle was a place where most people came to talk about things instead of doing them. That wasn't actually written into The Circle's articles of association, but it might as well have been.

Think of it this way, a Circle veteran might say. All big questions are long-term questions — ten-year questions at least. So if you say that you passionately support this or that plan for the general betterment of the world, the results of which will only become apparent in ten years' time, then, all other things being equal, people will assume that you are doing something along those lines. When the results are looked for in ten years' time and it turns out that you have been doing nothing of the kind, you will say, doubtless correctly, that the fundamentals have changed radically, that the problem is now a different problem, and that a different strategy is needed.

Olena suspected that just such a fate would await one of this year's sacrificial lambs, a “taskforce on international taxation to scale up development, climate and nature action”. It was to be the subject of a keynote plenary session featuring Greta Thunberg, and a by-invitation Ringlet for oil companies.

The name was a clunker, but the idea, floated at COP28, was logical, simple, and in essence incontrovertible.

Governments around the world were dispensing $7 trillion a year in fossil-fuel subsidies while the oil and gas industry was banking $4 trillion in profits, all due to the world's unfortunate addiction to carbon. Whatever the underlying problem, it was clearly not a shortage of money as such.

So why not redirect some of that $11 trillion toward large-scale action against climate change, action which was being demanded not only by the taxpayers who paid for the fossil-fuel subsidies, but also by the institutional shareholders who controlled most big public companies?

"Of course", Circle members would respond, while Greta Thunberg looked on expectantly. "But ... ".

And what came after that "but" would no longer matter. "But" meant "No".

To be fair on them, most members of the Circle genuinely did see private planes as something like a human right for those in a position to exercise it, a special case of freedom of movement.

But more than that, they saw governments, if not as enemies, then at least as predators, as institutions shaped by evolution to ingest money and power and then excrete it in inconvenient places.

Individual government leaders could be perfectly nice and intelligent. But anything that any government actually wanted to do, apart from privatisating and policing, was necessarily a bad thing, precisely because a government wanted to do it, and the consequence would therefore be more government. "Lovely idea", as they said at The Circle, "but sadly impossible to implement".

Still lost in her reflections, and in the darkness of the tunnel carrying her train out of Zurich, Olena momentarily caught her reflection in the window, and saw that the stress of the past few years had taken its toll. There were dark circles under her bright green eyes. But otherwise, on The Circle's scale of grooming, she was a 3.5, midway between "poised" and "polished".

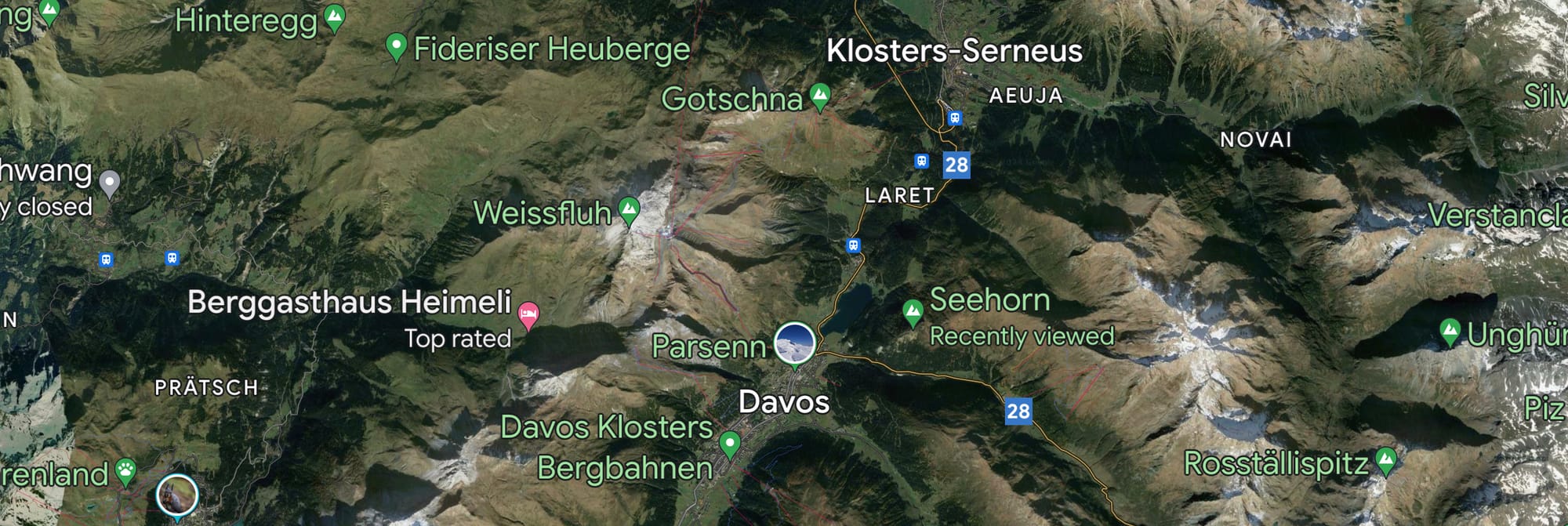

As the train finally emerged into daylight and left the last of the city behind, she looked out across the Zurichsee to the lush greenery of the foothills and the silhouettes of the Glarus Alps beyond. It was a magical moment — or would have been if an obsequious voice had not interrupted her at that very second.

"Ms Kostarenko?", the voice said. She turned to see a bespectacled man with a sad face settling into the facing seat across the table.

She responded with a curt "Yes" and a look intended to convey politely-veiled irritation at being disturbed.

"I am Alain Girard" the man offered, in lightly accented English. "We met on two or three occasions in London and Kyiv."

Now she remembered. Girard was a French journalist who parroted Russian propaganda about the war in Ukraine, not that he would put it quite that way. "One must see both both sides of an argument", he would probably say, in his flat, insistent, voice, as if reading from a script. If one "took the trouble to study the Russian perspective", one would would see that "repeated provocations" by the United States and Nato had "forced" Russia into conducting the "special military operation" simply to "ensure the security" of Russia itself. He was a creep.

"Can I ask you a few questions?" he said. Without waiting for an answer, he produced a pen and placed his own Starbucks coffee-cup on her table.

"I am sorry, but I have a lot of reading to do just now, if you don’t mind."

He wasn’t going to give up.

"Just one question, then. As a Ukrainian, where do you see President Zelenskyy a year from now?"

"Leading his country and leading it well, Mr Girard. Forgive me, but I have work to do."

He gave her a hard look which seemed to say that he, too, had a job to do, and his job was to talk to her, which made it her job to talk to him.

But apparently he was not going to insist.

"Too bad", he said, standing up and reclaiming his coffee. "Well, another time if I may. We have four days ahead of us in which to discuss this project of yours".

"I think that's my cup", said Olena.

He looked as if to check. "No", he said, "it's mine", and off he went.

Olena opened her book and stared pointedly at a random page until Girard was out of range. Then she looked around her. The carriage was full of Circle-type people, some of whom had packed as if for a polar expedition, judging from enormous suitcases cluttering the corridor. The volume of conversation was above the norm for a Swiss railway carriage. These were people accustomed to an audience.

From the corner of her eye she registered the sliding door opening at the front end of the carriage, and an elegantly-dressed man emerging from it with his arms stretched out in front of him, concluding a video call on his mobile phone. She recognised him at once as Karl Manhof, a German billionaire whose name was at the top of her checklist for the days ahead.

Manhof had inherited a family fortune amassed from coal mining, tripled it in tech, then pivoted into green investing. In 2020 he set up his Go Green flagship fund with a few hundred million euros of his own money, opened it the following year to friends and associates, and was said now to have more than five billion euros under management.

He branded and re-branded his strategy over the years using whatever buzz-words took his fancy. First, Go Green was "ESG-enthusiastic", then it was "impact enriching", then "sustainably stewarding", and, in Dubai, it was "building COPitalism".

Manhof was said to employ an analyst whose sole job was to track the shifting market premia attaching to words and concepts used in corporate mission statements, so that Manhof could literally talk up the value of his own investments and talk down those of his rivals.

Since Manhof usually travelled in a private jet with one of Go Green’s slogans, Greening>Faster>Together, painted along the fuselage, Olena was mildly surprised to see him on her train. But presumably his staff were posting videos from his mobile phone on social media as proof of his lifelong love-affair with public transport.

"Olenka, what a delightful surprise!", he announced upon seeing her. "You and me both walking the green talk on a Swiss train! We lead by example!"

His use of her diminutive was out of order, she thought, given that their meetings had always been strictly professional ones. Perhaps he was deliberately unsettling her. Or was he just being his over-confident, self-centred, m'as-tu-vu self?

"Good for you and well done us!" she responded, moderating her sarcasm.

Manhof sat in the same place that Alain Girard had occupied a few minutes before, crossing his arms on the table and bending towards Olena.

"So", he began. She wondered for half a second whether he had switched to German, but no, they were staying in English. "Let us compare notes", he said. "How is your to-do list for this week?"

He wanted to talk business. Good. She would give him her pitch. She assumed a formal smile.

"My briefcase" she began, "contains blueprints and term sheets for one hundred billion euros' worth of infrastructure projects, and that is just phase one. The government of Ukraine will announce the programme officially the day after a peace deal is signed.

"I won't try to give you the details here and now, but the key points are as follows. Everything will be underwritten by the EBRD. All tendering will follow EU regulations. All contractual disputes will go to international arbitration. EU-based bidders will get preference.

"The phase-one contracts are for a new international airport, a high-speed rail line from Kyiv to Warsaw, and the razing of the Chernobyl complex down to the last radioactive brick.

"Housing is also a priority, obviously, and power grids, and Black Sea port facilities. But those are areas in which Ukraine will take the lead. My agency's job is to define, prioritise and structure the projects which absolutely require international lead contractors."

Manhof nodded as though he dealt with things like this every day. "Exactly so!", he said, almost cheerfully.

Now it was his turn to set out his stall. "I said at COP in Dubai that Go Green stood ready to finance ten per cent of your programme, subject to detailed agreement on the public-private partnerships, and that I was confident other private investors would follow my example. I meant it, I haven't changed my mind, and I will say the same thing at The Circle.

"I will talk tomorrow about our moral debt as Europeans to the people of Ukraine, about the need for a sustainable Europe, about the interdependence of prosperity and peace, und so weiter. What I will not say is that the best time to invest is when there is blood in the streets, and, heaven knows, there is enough blood now in the streets of the Ukraine.

"I will not talk about blood and profit, because when I have a selfish reason to do something, and a selfless reason to do that same thing, then I publicise the selfless reason. People like me the more for it, and the ones who matter to me understand my reasoning in any case. I remind you of our Go Green motto: Do Good, Do Well, Go Green!"

By the time Manhof reached those last two words his voice was almost a shout.

Olena respected his realism. It was the truth, she thought, but was it the whole truth? She found it odd that Manhof wanted to get so deeply involved in Reconstruct Ukraine. The returns would be real enough once everything got off the ground, but that was five to ten years away. People who came from the green world generally thought long-term, but people who came from the tech world generally did not, and Karl had cut his teeth in the tech world. He must have a short-term angle. What was it?

Perhaps he was mulling a move into politics. In Germany, if you came into politics from the business world, they still liked to see a bit of dirt on your hands, the good kind of dirt. Karl in a hard-hat reconstructing Ukraine would play better than Karl in a Hugo Boss suit shorting the euro.

Or perhaps it was connected with something she had noticed when glancing over Karl's speech to the UN climate-change summit in Dubai. It used to be Karl's habit in every big speech to name-check the latest high-karma investor in Go Green — the Roman Catholic Church, for example, or the Danish royal family, or the estate of Albert Einstein. But in Dubai there had been no such revelation. Could it be that Karl was running out of new investors, and needed a new story?

They were passing Wallensee. The view was breath-taking, chiselled cliffs plunging into the inky-dark water. Karl beamed out at the landscape as though he owned it, which might well have been the case. Then he turned back to Olena.

"Nor am I so modest", he resumed "as to imagine that it is a matter of indifference to you whether I support your project in public, or not. If I commit myself to Reconstruct Ukraine, I do not say that others will necessarily follow me, but they probably will. If, on the other hand, I distance myself, even if I just say nothing, then in every future pitch you will have to explain away my absence."

He was right, damn him. She had no choice but to persuade him. "The numbers will be solid", she said. "And once we have private capital committed for at least half the work, then the EBRD underwrites everything. But there is a window here and it may not stay open for ever."

"Because Zelenskyy might go?"

"No, because Trump might come back. Right now, consolidating Ukraine is priority number one for the European Union and priority number two for the United States. How American priorities will change with a Trump administration is anybody's guess.

"If America pulls back, the Europeans will still be there and the European money will still be there in theory. But in political terms the foundations will have shifted, not least under Nato. So if we don't have a peace deal and a reconstruction plan signed before the next American presidential election, we don't necessarily lose everything, but we do lose momentum, and some governments may lose confidence."

She was trying to give Karl things he could agree with. He wasn't quite there yet.

"Of course I am on your side, Olenka", he said, once she had paused.

"Morally, economically, politically," he continued, "the world needs a stable and prosperous Ukraine. But are you quite sure that Europe has one view on this? When I hear Viktor Orban talking, and Robert Fico, I don't hear them saying that the European Union should spend its money in Ukraine. I hear them saying that the EU should spend its money in Hungary and in Slovakia.

"I am not saying that Orban can win the argument, I am saying he can drive up the price, he can get in the way. And, while we are on the subject of Trump, you won't hear this said out loud at The Circle, but plenty of our friends there did really rather well under the last Trump presidency, and they won't be quite as averse to his return as they might like to pretend."

Again, everything that Karl said was true, and Olena had prepared for it. Time to go deeper. "Let's call things what they are", she said. "We can go with the flow and find ourselves back in the dark ages. Or we can work towards a decent and democratic future. That future passes through Ukraine. The cost of rebuilding Ukraine is something that Europe can well afford. The cost of not rebuilding Ukraine may be the loss of everything that Europe values most".

Should she pause? Was she overselling? No, he was still listening.

"We must do it now, Karl. A road map for reconstruction will make peace possible before Trump changes the game. Next year may be too late."

Karl fidgeted in his seat and moved his hands across the table towards those of Olena. She drew her own hands back. He must not be allowed to embarrass himself. Not good for business.

"You need my support Olenka and you have it. But I also need yours."

Ah. Here came the twist. "What do you have in mind?", she said.

"I was talking to your colleague Sasha in Dubai about the advantages for everyone involved of incorporating a carbon certification mechanism into the Ukrainian reconstruction plan.

"The reconstruction will greatly increase energy efficiency in Ukraine and greatly reduce carbon emissions. I propose that stakeholders should monetise at least part of those gains in a front-loaded sale of carbon credits through a market mechanism. I want to confirm that Sasha mentioned this to you, and that you are not opposed to it."

The twist was not a welcome one.

"Sasha did give me a note on that subject. And I believe, as a matter of fact, that you know my own view. Creating and trading carbon credits can take place credibly only where there is an advanced legal system, expert scrutiny, and effective enforcement. Until and unless those conditions obtain in Ukraine, a licence to certify carbon credits there, which I think is what you have in mind, would resemble a licence to print money, and bad money at that.

"I am not opposed to the principle of carbon trading, obviously. It is EU policy. But existing carbon markets have more than enough reputational problems even where effective regulation is supposedly in place. We should be seeking ways to eliminate historic corruption from post-war Ukraine, not introducing new ways for Ukrainians and foreigners to corrupt one another."

"That’s a bit harsh!"

"It is, and it isn’t. We can set all the net-zero targets we want, but if we can’t document them reliably they won't deserve to be taken seriously. And if we then start certifying carbon credits which may or not reflect real metrics, when even the supposedly real metrics may or may not have been measured reliably in the first place, then the end-result will be that European taxpayers get their pockets picked."

"But Sasha was rather in favour of the idea."

"So am I, Karl, in principle. Eventually. But we are working in a long-term framework, and you are looking for short-term returns. If we do set our scruples to one side and say yes to junk offsets, word will soon get out that half the paper is bogus, the blowback will be horrible, and we will be sitting up there on our moral high ground looking like swindlers and idiots."

At that very moment, a kerfuffle broke out at the far end of the carriage. Passengers were gesticulating furiously about something that had happened outside Olena's line of sight. It sounded like something serious. She and Karl got up. What on Earth was going on?

A horrible sight awaited them when they moved closer. A man whom Olena recognised as Girard, the French journalist, was doubled up in apparent agony on the floor of the train between two rows of seats in a pool of his own excrement. His face was locked in a grimace, his body was twitching with repeated spasms.

The number of onlookers increased. Those at the front struggled to keep a safe distance. For a moment there was silence, save for a man at the back who was calling somebody, the emergency services perhaps, on his phone. Somebody else had pushed the emergency button. The smell was unbearable. Girard was continuing to twitch, but less violently now. "Has anyone called the police?", asked Olena. But already the train was pulling into Landquart station, and there on the platform the police were waiting.

To be continued tomorrow ...

If you're already a Browser member, please join the special Death In Davos newsletter by updating your subscription options here; otherwise, just enter your email in the box below.