Death In Davos: Day Four

By "Emily Adjarian"

Author's note: This serial is a work of fiction. The people and events described in it spring directly from the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actually existing people and events is entirely coincidental.

Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six | Day Seven

Speculate and debate on Discord here.

Tuesday 16th January 2024 — Davos

IN THIS EPISODE: Philip vanishes | Sandra almost gets sacked | Colonel Bern stands up to The Doc | Rebecca Stilton's secret | The Doc sheds a tear | Olena expects a very important visitor | Karl shows his hand | A head explodes

Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five

THE DOC stared into his emerald-green Mountain Morning Maxivitamin smoothie. His inner composure was shaken as thoroughly as the drink itself. He couldn’t think straight, he couldn’t hold a thought, except for the very thought that he was trying not to hold: That this, just possibly, could be the beginning of the end.

Everything at The Circle was meant to look effortless, for White Badge holders at least. They put themselves in the hands of The Doc, and The Doc massaged their egos as only he knew how.

With each passing year the annual meeting, like a work of art, had acquired its own patina, a finely lacquered surface in which members could see their visions of themselves reflected. If the patina were to be cracked by some catastrophe, this year or any year, the crack would be visible for decades to come, which might as well be for ever as far as The Doc was concerned.

And this year, at this meeting, every hour seemed to bring another blow. The autopsy on the helicopter pilot had revealed apparent traces of drug use. Girard's phone was full of text messages which the police declined to disclose even to The Doc. And now it was Philip. Philip Middlewait was nowhere to be found. How could The Doc's own chief of staff vanish into thin air just when he was needed the most? Had Philip been the next victim of this thing?

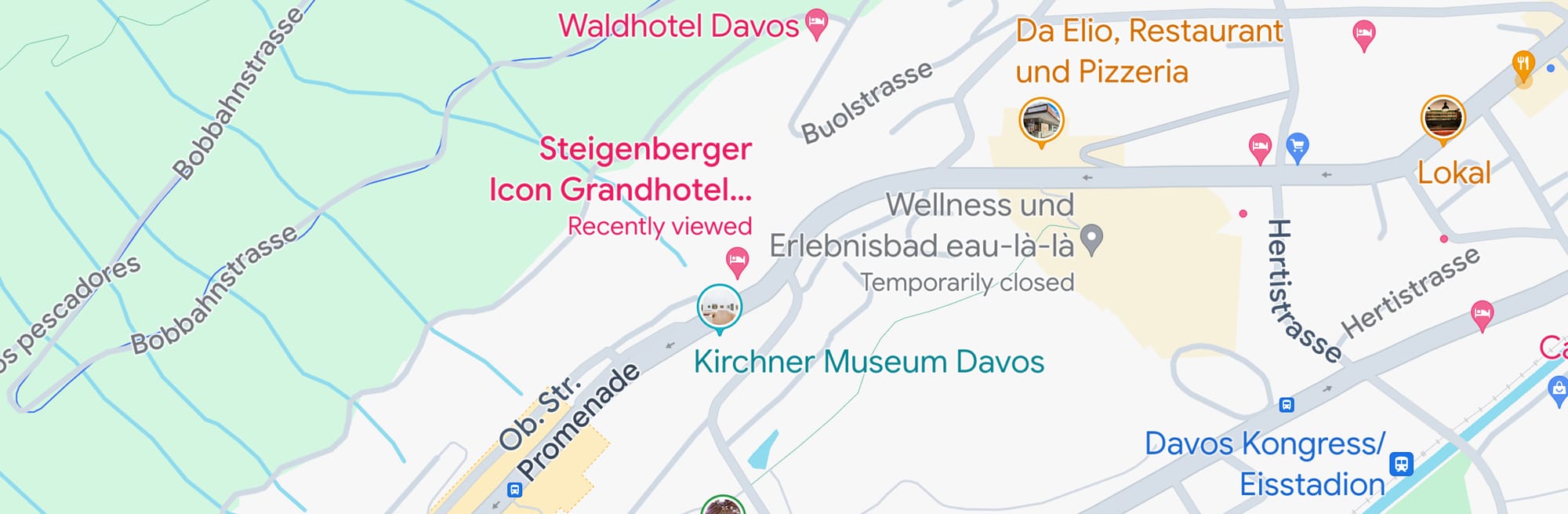

Philip had failed to show up at Tuesday's 6am senior staff meeting, and nobody had the faintest idea why he was not there, nor where he might be. By 10am, at the request of Markus Bern, The Circle's security chief, police dogs were scouring the snow-clad streets of Davos in vain. A search of Phillip’s apartment had yielded nothing of possible value save for his Circle mobile phone left on the bedside table. Philip had simply evaporated, and contrived to do so in what was, at this particular moment, the most thoroughly surveilled place on earth.

A sense of rising panic was gnawing at The Doc's innards. Until that morning he had been able to insist successfully to himself that Girard and the helicopter crash had been a coincidence, or, at any rate, that he was fully justified in proceeding as though they were a coincidence.

Now, with Philip gone, The Doc felt sure that these were not coincidences — that he and The Circle were under attack. No longer could he maintain his zen-like calm when he gave instructions to Sandra and Markus or briefed to other staff. Now he was issuing his orders in tones of desperation, most of them consisting of a single word: "No".

When Sandra Smiley, his director of communications, had proposed a minute of silence at the closing plenary session for the victims of the helicopter crash, The Doc had almost sacked her on the spot, until his common sense got the better of him. What use was a director of communications when the priority was to keep things quiet? Where could he find a director of non-communications? How long could the news of Phillip’s disappearance be kept under wraps? How could he do anything without Philip?

It was still business as usual in most of the Congress Centre and the rest of the town, though a practised observer might have noticed an unusually large number of dark-suited bystanders around the place dissembling a keen interest in the middle-distance.

White Badge holders bustled through the inner corridors of the Congress Centre; coloured-badge holders drank coffee in the all-comers bar and studied the programme; plus-ones and vice-presidents idled in hotel lobbies, made restaurant bookings, and shopped for woolly gloves. Everybody was talking business, planning deals, exchanging New Year greetings and hugging haven't-seen-you-for-ages friends.

The accredited media, however, and the unaccredited media even more so, were visibly frisky. Rumours were circulating, and new details were being hazarded, both about the helicopter crash and about Alain Girard's death.

One journalist had talked to a passenger in Girard's train-carriage who had given a first-hand account of Girard's spasms and soilings. Another had a found a source inside the Swiss police who had said something which the journalist was keeping to herself, about the helicopter pilot. A third had been on the Promenade when the helicopter came down, and knew that helicopters did not crash quite like that.

The economics correspondent of The Guardian, charged for once with a general news story, was ready to go that night with a piece saying that the Swiss police were "expressing doubts" that the two incidents could be a mere coincidence, given the place and time. She was also aware of Girard's record as a Putinist sympathiser, and would throw that into the mix.

The New York Times Dealbook correspondent planned a different take, one that would have tormented The Doc even more if he had known it was coming. Was it wise, the correspondent would ask, given the current state of the world, for hundreds of leading figures to gather in the same place at the same time, in such numbers that even the Swiss police and Swiss army could not possibly protect all of them all of the time?

Conspiracy theories about the helicopter crash had reached The Doc's ears, but none yet seemed to incorporate hard leaks from the pilot's post-mortem. All the same, you didn't have to be Machiavelli to deduce that a verdict blaming the crash on a drugged-up pilot would suit the world's aviation manufacturers down to the ground, as it were.

Markus was tracking the staff gossip, which centred mainly on the supposed elimination of one of the helicopter's passengers — either the investigative journalist from Ukraine, or the British "philanthrocapitalist" (even The Doc hated that word), Rebecca Stilton.

Stilton was a regular at The Circle, but this year, apparently, she had an agenda of her own, or so her recovered mobile phone revealed. She had invited a dozen other White Badge holders to an off-the-record breakfast at the Magic Mountain Spa for something that was apparently going to be called the “Dump Trump” caucus.

This last news enraged the Doc. He summoned Markus for a one-to-one. "Why didn’t I know anything about this group?", he demanded. "Obviously we cannot interfere with what people do in their own hotel suites. But nor do we want the newspapers saying a year from now that a coup against the president of the United States was planned at The Circle. It will be the oligarchs all over again!"

"I conducted a provisional investigation", began the head of security, flipping through the pages of a notebook, "in which I cross-referenced the known engagements, the unallocated diary-time, and the records of known telephone calls — metadata only — between the White Badge holders who were invited to Ms Stilton's breakfast, and others with whom they as a group were in frequent contact.

"My inference is that a particular group of perhaps two dozen or more participants have come to Davos primarily to conduct a preplanned series of private meetings, in various configurations, with one another. Given the nature of Ms Stilton's planned breakfast, we may presume that their main purpose is to organise against Mr Trump’s re-election.

"To answer your question, Herr Doktor, we had no way of knowing that such activity was under way, because we have always concerned ourselves solely with what happens inside the Congress Centre. We leave what happens outside the Congress Centre to the attention of the Swiss police. Apparently the police had no word of this. Nor, I think, would they have seen any grounds for action if they had known about it."

The Doc was suddenly furious. At any other time he would have understood that there was nothing that he could or should do save perhaps for fine-tuning next year's guest list and locating a friendly informant within this supposed caucus to tell him what was going on there. Knowledge was power. But this was not any other time and he was losing his self-control.

"Who gave you this information?", he demanded. "What else do they know and how do they know it?"

"My contacts in the Swiss services shared this information with me. I have no concrete knowledge of their technology for interrogating mobile telephones. If I were to ask for further information, and thereby to hint that we were considering some action of our own, I believe the effect would be most counter-productive, both in this instance and for the course of our future working relations with the police, which have always been excellent. But of course if you want me to take that action then I will do so.

"I am not even sure", Bern continued, "what other details there could be. This does not seem to be an organisation as such. It is a group of people who have every right to discuss their perfectly legal preoccupations, and who may well have many things to discuss besides the particular topic with which we are now concerned. I imagine that they would be justifiably indignant if anybody challenged their right to do so. At the very least they would move their discussion elsewhere."

The Doc slammed his fist on the table. He was on the point of raising his voice still further, of shouting at Bern, something to the effect that Bern's job was to do what Bern was paid to do, not to offer opinions on matters that he did not understand. Then The Doc checked himself. Inwardly, he backed off a step or two. There had been times often enough when he despised his subordinates for not having minds of their own. Now, here was Bern was talking back to him — and, The Doc had to concede, Bern was making sensible points. The man had unsuspected qualities.

The Doc decided to withdraw gracefully. "Please try to confirm how these people are otherwise connected, but discreetly", he said. "My legitimate concern is that the name of The Circle should not be associated with any political platform. We are not the Brookings Institution or the Heritage Foundation. We do not seek to be a associated with any political current. Perhaps I am over-reacting in this particular case. I have a lot on my mind."

"I understand. Thank you, Herr Doktor."

The Doc, left alone, stared at the wall. He was suddenly feeling old and tired.

When explaining The Circle to people who did not see how it could not be political, one way or another, The Doc had a favourite analogy.

In a democratic country you had a constitution. You also had political parties. The constitution contained the principles on which everybody, including the political parties, could agree. The constitution allowed the political parties to say what they wanted to say, within the limits of the constitution. The Circle operated at the level of the constitution, not at the level of political parties.

And yet, and yet, thought The Doc. Perhaps it was only with hindsight that one came to recognise the most important characteristics of the times in which one had been living. And only quite recently had The Doc appreciated the extent to which there had actually been a desire for consensus, a world order of sorts, to which The Circle could attach itself, at least until ten or fifteen years ago. Now, not so much.

You might go back further. There had been a shock to the system on 9/11, another with the invasion of Iraq, then 2008 — but even then, most people, in most of the world, had gone on thinking that working together, getting along with one another, was a useful and desirable thing. Win-win. Now, not so much.

Trump alone had had not changed everything, but Trump and Putin and Xi and Erdogan and climate change had changed everything, and they were symptoms as well as causes. No longer did The Doc detect any universal attachment to any semblance of world order. Everything was crisis and conflict, all the way down. The whole world was made up of states of exception, to use Schmidt's term. People truly hated one another in a way that had not been seen since 1945.

The Doc's public conversation with Trump, when Trump came to The Circle a few years back, had left a bad taste in his mouth. Not only because Trump was personally so unpleasant, though The Doc would have struck him from the guest list were he not President of the United States. It was more because, after the conversation, The Doc had heard people say that he had been too deferential to Trump, sycophantic even.

"Well it wasn't me who elected him President", The Doc's first reaction had been when he had read the press comment on the Trump session. "Are they saying that we shouldn't invite the President of the United States to The Circle? And are they saying that we should be rude to him when he comes?"

At the time, it had not occurred to The Doc that it would have been anything but folly to invite the president of the United States to The Circle in order to criticise him, or not to invite the President at all when the President was minded to attend.

But cui bono, when The Circle gave dignity to demagogues? Would The Doc invite the AfD to The Circle, and be respectful to them, if they won a regional government in Germany? Would he have Putin back, once peace was restored? Would he disinvite the Dalai Lama if Xi Jinping suddenly wanted to attend?

The Doc had intended The Circle to be above ideologies, but now there was no "above". Everything in the world had been ideologised. If you tried to escape ideology, ideology came looking for you, and in the end it found you. He felt towards Putin and Xi the same way that George Soros must feel towards Viktor Orban: "I taught you how to use your knife and fork. I taught you how to sit at table. And now you spit in my soup."

Around the same time that The Doc was inwardly cursing the leaders of the unfree world, Olena had come to the end of her day of back-to-back meetings in the Hotel Belvedere. There were worse places to do your meetings.

Karl Manhof, her seemingly loyal hedge-fund tycoon, had said that, since he was now her anchor investor, and since Go Green was proposing to match, euro for euro, all the public funding that went into Reconstruct Ukraine, Karl considered himself part of the Reconstruct Ukraine team, and he expected to join all of Olena's meetings in Davos.

She was taken aback, but she decided to agree. There was nothing confidential in her pitches. All the terms and conditions of the tenders would be public. To have Karl alongside her at her meetings would be a net plus. So Reconstruct Ukraine set up shop in the reception room of Karl's suite at the Belvedere, a suite which, when the last delegation had departed, he began praising as an example of his own good taste.

"You are thinking: Why such modesty? Why only the Thomas Mann Suite?". He waved at the hundred square metres of carpeted floor which surrounded them. "Why am I not in the Gorbachev Suite, or the Kashoggi Suite, or the Nursultan Nazarbayev Presidential Supersuite?

"Because it is too easy to show off here. Let everybody else do that. I will top them all by not competing. You see, Olenka, I do not want people to admire my wealth. I want them to admire my taste".

The arrogance of the man! She wanted to tell him to stop using her diminutive. Or call him "Karlchen" and see how he liked it. But given the child-like sense of entitlement which pervaded everything Karl did, he might well like it very much, and then where would they be? She reined herself in. She needed his money. She needed his goodwill. She needed to put up with him.

They had spent most of the day discussing phase-one projects — the airport, the high-speed rail, Chernobyl — with delegations from countries and organisations that had already promised to support Ukraine’s reconstruction.

She gave the same pitch each time. And, each time, Karl added his pledge to match public money with private capital. She and Karl enacted excitement in front of each new interlocutor about the "sustainable Ukraine" they would build: Energy-efficient infrastructure, ultra-low-carbon industry, high-speed railways in place of traffic-jammed roads, rewilding where Chernobyl once stood, an international airport for the first generation of electric-powered aviation.

And, each time, the same closing closing remarks came back across the table: "We will look at this with utmost seriousness". "Ukraine’s future is our future". "You have our full support". "Please keep us updated".

It was past 6pm. Olena stood up, muttered a compliment to Karl about his suite, stretched, sighed theatrically, and said in an end-of-day voice:

"My summary of progress to date. If Ukraine could be reconstructed out of lame assurances, we could turn Kyiv into Manhattan tomorrow."

"That’s a bit harsh!", said Karl, in one what evidently one of his favourite phrases.

She was not blind to the fact that Karl had successfully manipulated her. She was treating him as a colleague when she should have been treating him as a counterparty. But it was too late to undo that now, and, in any case, his insights were useful. Perhaps she could provoke more of them by pushing him a bit and looking for the moments when he dropped his smile.

"Let’s face it, Karl", she began. "On the train down here I gave you my pitch, the pitch you have heard me giving over and over again today. Let's you and me zoom out.

"I know, and you know, that the Americans and most of the Europeans are cutting back on military assistance and even economic assistance, to Ukraine. If that continues, who is going to be queueing up to invest in Ukraine at all, let alone in a 'green and sustainable manner'? Why board a bus if it isn't going to move?

"Ukraine will never willingly agree to a peace treaty without a guaranteed reconstruction programme, and nobody is going to sign off on a reconstruction programme without a peace treaty ready to be ratified. How do we square the circle? I am not speaking on behalf of the Ukrainian government, this is me talking because I need to think this through."

"Listen", retorted Karl, with his self-confidence unruffled. "The optimal outcome is a fully-funded reconstruction programme, so we work for that outcome. Nobody ever wants to go first, so I have gone first. Already you are in a stronger position than most people with a dance-card to fill.

"I have my reasons for supporting you, and I have shared them with you. As it happens, I don’t think the Americans will let you down. Also, I have reason to think the Germans are more open to persuasion than you seem to assume, so long as it is done in an appropriate way. Scholz is not Merkel. He is not thinking a century ahead, he is thinking three months ahead. In the end he will do what the newspapers tell him to do.

"And besides, the three Americans who came this afternoon seemed pretty keen. It's actually a positive for American financial investors that the tenders are designed to favour EU contractors, because that means a smaller circle of qualified bidders, the bids will therefore be higher, and the margins on those bids will be higher. Americans don't really want to invest in Ukraine, you must see this, they want to invest in the European companies that will win the tenders."

Another piece of Karl's calculation fell into place for her. Nobody could know ahead of time who would win the tenders, but Karl could was putting himself into a position where he would know better than anybody else who was likely to win the tenders. He could invest accordingly, and people who understood Karl's positioning could invest through or with Karl.

"But the Americans will want to say that they are investing in Ukraine, and we can give them that", Olena said. Karl nodded approvingly. "Look, Karl. You have may heard this. I am not supposed to tell anybody, but it is hardly a state secret. President Zelenskyy will be here in two days for the closing day of The Circle.

"Zelenskyy", she continued, "will set aside one hour to see people that I want him to see, people who will commit to the reconstruction, or, better still, have already committed. You will get an invitation, obviously. I need Zelenskyy to leave here feeling good. I need him to start talking about the reconstruction as though it is something real, as though it is his own legacy. I want him to win the war, however that works at this point, but I want him to plan for the peace."

"Patience!" smiled Karl. "Two days is a long time in Davos. You will see twenty more people tomorrow, all of them with something to offer. If they say that they are supportive, ask them for letters that you can pass on to Zelenskyy, letters in which they say how much they support the reconstruction, how much they look forward to working with Ukraine.

"A letter commits them to nothing. But then you arrange for the writers of the strongest letters to meet Zelenskyy. They will want to meet him, and they can hardly say then that they have suddenly got cold feet, or that their level of commitment has been misunderstood, when he has their letters in his hand.

"Among the people we saw today you should ask for such a letter tonight from the USAID representative. And from Bouygues. And from that American Senator who seemed to think that there were contractors in his home state who would want to be considered, and who promised help in Congress."

She stared at him with an air of disbelief. Would she ever dream of telling him how to run Go Green? But actually, it was a sign of her fatigue that she hadn't come up with a strategy like that herself. Also of her underlying depression.

She had listened to The Doc the previous night and she had felt as though she and The Doc were synced on some telepathic wavelength. She knew that he was saying one thing and thinking another. He was going through the motions, he was performing for them all, like the orchestra that went on playing when the Titanic went down.

Maybe the orchestra was hoping that the Titanic would miraculously right itself, or the musicians didn't know what else to do, or they thought that history would appreciate the gesture.

That was the vibe she had got from The Doc last night, the dog-whistle she heard him blowing. It was something about his facial expression, or his tone of voice, when he made his stock references to tragic violence and unprecedented uncertainty.

She remembered those formulae from her days as an Aspiring Leader. But she felt now, and she knew somehow that The Doc felt this too, that very soon there would be nothing left in the world except tragic violence and unprecedented uncertainty. The Doc needed to cry wolf for real, there was a giant herd of wolves covering the whole horizon, but he had devalued his words so much by over-use that they no longer alarmed anybody and he had no new words to replace them.

As for Olena, whatever she might say in her pitches, she was now certain of a Trump victory in November, and after that a final lurch into global chaos. She had come to understand belatedly that most Americans in most parts of America actually wanted a president like Trump. His previous victory had not been an aberration or a misunderstanding or a one-off protest vote. The American id had found its spokesman and was delighted with the results. Biden had been a reflexive spasm, a posthumous twitching of liberal democracy, but it had not been nearly enough. The future, absurd as that sounded, was Trump.

"I’ve written off the US", she said suddenly to Karl. If the world was going to end, she decided on impulse, no sense in pretending. "The odds of Trump winning are high. The odds of the United States becoming a de facto dictatorship are significant. Then we are f—ed. No more NATO, no more this, no more that, no more Ukraine. If that doesn't happen now it will happen soon. The trend is decidedly not our friend, my friend."

Karl looked at her quizzically. Was this a gambit of some kind, or an honest outburst? In either case, his response would be the same.

"‘Olenka!", he said. "People have a remarkably bad record of prophesying the future. They do not even understand the metaphysics of it. When The Doc talked about 'unprecedented uncertainty' last night I wanted to jump up and object. The only certain thing about uncertainty is that it is never unprecedented. Uncertainty is always present and always absolute. Uncertainty describes a situation in which not only the outcomes, but the model itself, are unknown — and if you or The Doc knows God's model for the Universe I take my hat off to you both.

"One must never confuse uncertainty with ranges of possibilities or degrees of probability or absence of data. They are quite different things. The Doc has forgotten his F.H. Knight. And, quite besides that, one must always oppose the inevitable, because if one does not oppose it then one will never know how inevitable it truly was."

She had to smile. She had been right to sound off. He had not only wrapped her despair into a neat little package, but had returned it to sender with a ribbon on top. She shook her head to indicate that the incident was best forgotten, looked at her watch, and saw that it was 6.45pm.

"Let’s call it a day. In fact the Senator has texted me asking me to join him for a drink downstairs. With his wife."

‘There, you see. Things aren’t as bad as all that!’

Olena bundled up her papers. In the lift down she started scrolling through her unopened emails and messages. Her WhatsApp screen was full of ex-colleagues from The Circle asking her whether she knew anything about Philip. Apparently Philip had disappeared and nobody knew where he was. The consensus chatter was that his disappearance was a non-trivial part of an emerging pattern of bad things. As one message wondered: "has he he found them or have they found him?".

She took her puffer jacket from the coat rack, rummaged through the pockets, and found the number that Philip had given her on Sunday. She couldn’t be late for the Senator, but she needed to make the call. She downloaded the Signal app, which was new to her, then send him a message: “p: how are you and where are you? please respond. olia”. Off it went, and on she went to find the Senator.

The lobby was packed. Dozens of Circle guests were leaving, the men in black tie, for a plenary dinner at the Congress Centre. A queue of cars waited for them in the icy courtyard, advancing one by one for pick-ups at the hotel door. Beyond the colony of penguin look-alikes Olena spotted the Congressman, his wife at his side. She went over to them and shook their hands.

‘How very nice to see you again, Mr Senator, and to meet you, Madame ...’

"The pleasure is mine, Ms. Kostarenko" he interrupted. "Please call me Ishmael. It happens to be my name, unfortunately. My parents were literary types. Where shall we go? Do you have a recommended spot?"

She expected him to have somewhere in mind, but she knew exactly where she herself would prefer to go: to the Peeperkorn Bar, on the far side of the lobby. It would be relatively quiet, given that so many people were going out to dinner. They played only the gentlest of background music in the bar, which was important to her. Conversations were delicate things and should not be interrupted unnecessarily. She liked the look of the Senator and his wife. They could become real friends. Useful friends too.

"If it would suit you both, let me suggest that we stay here in the Belvedere and ...

That was as far as she got. The Senator's head somehow exploded. Glass shattered somewhere nearby. The Senator's wife screamed. Then Olena screamed. Then everybody in the lobby screamed.

The Senator seemed to fold up and tumble sideways. Two seconds later he was flat on the carpet with blood pouring from his head and his wife kneeling beside him. She was weeping, then shouting, then muttering, looking at the Senator and then looking around for help.

Four men appeared beside them. Perhaps the men had always been in the lobby and she hadn't noticed them. They were wearing dark suits and they had guns in their hands. One of them was talking urgently into an earpiece. They were police.

Two more plainclothes officers arrived, then another two, and another two. They formed a ring around the dead man — for dead he surely was — and gestured the bystanders to move back. An ambulance arrived outside, lights flashing. The crew raced in, put the body on a stretcher, and took the stretcher out to the ambulance.

Two policemen escorted the Senator's wife into an unmarked car which pulled up in place of the ambulance. The car drove away in pursuit of the ambulance. Two policemen stood with Olena, one on either side. They asked her to remain in place for moment, and would she like a chair? She would. She was shaking violently. She was terrified.

Twenty minutes later Olena was alone in her own hotel room with a police officer outside her door. The police had driven her there, verified her identity while she was still in the car, and asked her what she was doing with the Senator. After she had managed to put a few sentences together, she was escorted up to her room and invited to rest. A nurse would be with her shortly. The police would talk to her again when the shock had passed. And, in the meantime, if she remembered anything about those one or two minutes before the Senator was shot, when she was standing next to him, or anything else that she had noticed in the hotel lobby, she should she write it down. They gave her a notepad and a ballpoint.

She looked at her phone. Markus Bern had called her. The Doc had called her. They must have heard. They must know she was OK. She didn't want to talk to them.

The only person she wanted to talk to was Philip. She opened Signal and saw a message from him, timed at 6.52pm, in reply to her own: "i am fine olia but off grid in coming days. take good care".

With trembling fingers she typed: "man shot next to me just now. senator. need advice. please help".

She watched while Philip messaged back to her: "presume you now in hotel and police with you. if so go nowhere. if not call bern. i will tell you what to do next".

Tell her what to do next?

She sent off another text: "please explain how you know what is happening".

Philip again: "i know things other people do not. not all but some. please trust me".

Then he was gone.

At the hospital, the Senator was pronounced dead, and his wife wept again. At the Congress Centre the dinner came to its end and The Doc was quietly informed that police and soldiers were saturating the streets leading from the Centre to the Belvedere and to a few other big hotels.

At the Schweizerhof, the nurse arrived, the police officer let the nurse in to Olena's room, the nurse injected Olena with a sedative, and within minutes Olena was asleep. A dreamless sleep, thankfully, for her dreams would not have been pretty.

To be continued tomorrow ...