Death In Davos : Day Five

By "Emily Adjarian"

Author's note: This serial is a work of fiction. The people and events described in it spring directly from the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actually existing people and events is entirely coincidental.

Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five | Day Six | Day Seven

Speculate and debate on Discord here.

Wednesday 17th January 2024 – Davos

IN THIS EPISODE: The balloon goes up — Davos in lockdown — Snipers at large — The Doc appeals for calm — A catastrophic error — Anger mounts — Rebellion in the Congress Centre — Poor Mr Massover

Day One | Day Two | Day Three | Day Four | Day Five

THE DOC liked to talk about "Circle Moments" — things that could happen only at The Circle, like being there when Xi Jinping was playing the piano while Sinead O'Connor was singing Moon River, or seeing Lyndon LaRouche in the Belvedere Bar sharing jokes with Kathy Acker and Angela Davis. But, as Circle moments went, this one was off the scale. It had started on Tuesday night and seemed as though it might never end.

When the the gala dinner was winding down at the Congress Center on Tuesday night, the police took The Doc aside. Half an hour later, when most guests should have reached their hotels, an urgent alert was issued in The Doc's name on LiveRadius, The Circle’s messaging app, asking “all participants” to remain in their hotel rooms. If they were not in their hotels they should go directly to their hotels. The Circle "regretted the inconvenience", but was "following police instructions", and "recommended" that everybody do likewise.

The hundreds of guests walking or cabbing back to their hotels from the Congress Centre saw that something was up, well before they saw The Doc's alert. Armoured vehicles stood at every street-corner. There was a soldier in combat gear every five meters or so along the pavements. Helicopters were clattering through the skies, sweeping the mountains with spotlights. Outside the Belvedere a cordon had been erected and arrivals were being funnelled in through a side entrance.

If the intention was that people should go straight to bed, the result was rather the opposite. Inside the hotels, and at every bar around the Congress Centre, until those bars were closed by the police, people were drinking into the early hours, checking their phones, and comparing notes on what they had heard; in a few cases, on what they had seen.

The Circle hadn’t been this interesting for years, people joked; after which they went on to agree that, actually, it wasn't that great if people were getting killed; the sessions would be disrupted and they had come all this way; the Swiss Army wouldn't be mobilising unless something big was happening; and maybe this wasn't an amusing situation after all; in fact, maybe it was vaguely scary to find yourself in the middle of a near-war zone when you had brought your other half along and you were planning to talk business and catch up on some skiing. But at least they were all in it together, which was a good thing, except, you know, if it wasn't a good thing, if it made them all a target, and apparently the New York Times was running a piece saying something along those lines.

Everybody on social media was debating the timeline. First, somebody had been poisoned on a train from Zurich to Davos on Saturday — not a somebody whom anybody in the Belvedere Bar knew personally, but somebody who was coming to The Circle, anyhow.

Then there was the helicopter crash on Sunday. A tragic accident, and maybe now it wasn't an accident. And that paled beside the two shootings which occurred hours ago while people were heading for dinner. A US Senator was killed right there in the lobby of the Belvedere. The CEO of a major American bank was shot dead a few blocks away.

It had been a sensible move, they agreed, to allow them all to return to their hotels after dinner while the killers were still at large and the streets were being flooded with soldiers. Kudos to The Doc and to the Swiss. Anywhere else they would have been shut into the Congress Centre for the night while the police locked down the town.

And what was going on? Maybe there was one real target — some thought the bank CEO, others thought the Senator — and the rest were red herrings. But it was a hell of a red herring to bring down a helo; and killings this good were expensive. There were people who knew about this sort of thing, which is to say people who had people who knew about this sort of thing. If it was just the bank CEO or the Senator that the bad guys were really after, they could have got the job done for — what — "a hundred thousand bucks" somebody hazarded, and not under the noses of the Swiss police either.

Whatever was happening here was costing somebody millions if they were paying market. It had to be terrorism of a highly organised kind. Sure, plenty of people talked about The Circle being a conspiracy to run the world in league with Bilderberg and the Trilateral Commission and the Rockefellers and the United Nations. But did any serious player have the money and the stupidity and the motivation to act on that insane theory? And if they did, what was the endgame?

The details which trickled out during the night did nothing to calm anybody's nerves, nor did the smell of soap from the Belvedere lobby. Three hours after the shootings, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung was saying on its website that each of the victims had been hit with one 7.62×51mm NATO round, probably from a considerable distance. On a windless night a bullet like that could carry more than a mile.

What that strongly implied was that these shootings were planned long in advance and had involved at least four highly-trained hands-on professionals — two expert snipers, each with a spotter to make the wind call. So long as they had a line of sight, the shooters could have been anywhere at all, with all the time in the world to break down their guns and move on before the police could even begin to guess at the trajectory of the bullets.

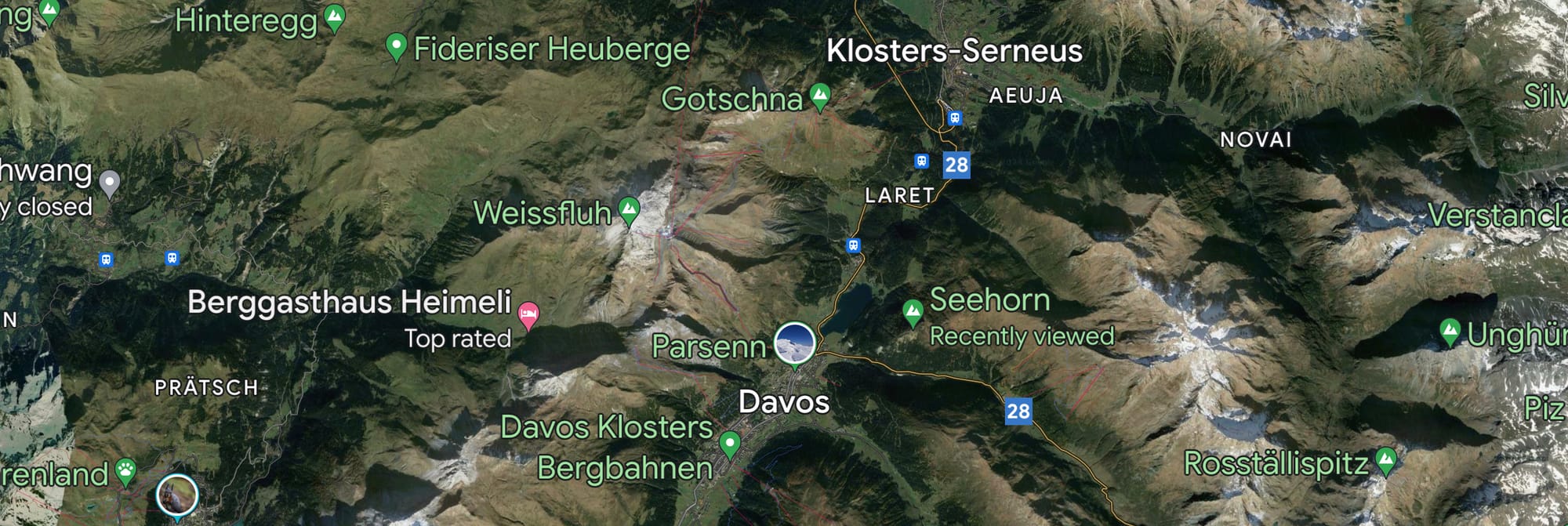

Those staying in the Belvedere were soon congratulating themselves on their choice of hotel. A contingent which ordered a minibus to take them from the Belvedere Bar back to the hotel at which they were staying in Klosters, ten kilometers along the valley, reappeared in the Belvedere Bar half an hour later. The police had sealed all exits from the town. The valley was closed in both directions.

They were cut off. They were role-playing an Agatha Christie mystery. Where was Hercule Poirot?

The novelty of the situation took the edge off what might otherwise have been some early indignation. A representation to the concierge of the Belvedere, who had temporarily relocated his perch from the lobby to the corner of the bar, returned with the information that the Belvedere had no more rooms, which they all knew; but also that, according to the hoteliers' intranet, no other hotel in Davos had any rooms, and all airbnb listings had been mopped up months ago.

The Belvedere Bar rapidly turned into a clearing-house of sorts, as did many other hotel bars. People with suites offered up their spare rooms; a few with twin-bedded rooms offered up their second beds; many bad jokes were made; the concierge announced that the Swiss army would shortly be making a delivery of camp-beds which would be installed in the hotel ballroom. Never in the history of The Circle had there been such a sense of Gemütlichkeit among members. Nor would this one last beyond the morning.

In the course of the night a few mutinous guests tried to outsmart the police, deciding after one-too-many drinks to slip out of the valley on foot or on skis. No chance. The Flüela and Wolfgang passes on the Klosters side were heavily guarded and closed to any kind of traffic – trains, cars, people, even skidoos; as was the Albula pass at the other end of the valley.

Around 2am one clutch of hedge-fund managers resolved to ski-tour their way over the Strela pass. "Not a problem", insisted their ringleader, who had been bragging to them about his ultra-trail exploits around Verbier. "All of us are fit. Some of us are super-fit. Any stragglers, I'll pick them up and carry them myself. Cherry on the cake: I’ve ordered a limo minivan that will be waiting for us near Klosters. We’ll be at Zurich airport by lunchtime."

A Swiss investor in the group who also happened to be a reserve officer in the Swiss army advised otherwise. He pointed out that this pass would also be closed, as would all other high-altitude routes including the Sertig and Scaletta passes. The Swiss knew where their mountains were and they knew where their mountain passes were. Every viable route, and more besides, would be under close surveillance by the Swiss army’s mountain troops, and probably also by members of the AAD10, the special-forces unit. Another round of schnaps was ordered.

On Wednesday morning a meaningful proportion of White Badge holders awoke with a hangover. An alert on LiveRadius invited them to attend an "important information meeting" in the Congress Centre at 9am. It had not been a dream.

They trudged in twos and threes to the Congress Centre, passing the soldiers and armoured vehicles still stationed along the route. The sun was out, and so were some gizmos that no visitor had ever seen before: revolving motorised mirrors on tall stalks, flashing the reflected sun towards the neighbouring mountains, in case any sniper out there might be planning another shot.

Well before nine the plenary room in the Congress Centre was full. So, too, were adjacent rooms, connected via video to hold the overflow. The atmosphere in the main room was one of impatient hubbub. These were not the sort of people to whom this sort of thing was meant to happen. Ever.

At nine precisely the Doc appeared on stage, looking out at the room. The fuss slowly subsided. He was stiffer than usual, hesitant, distinctly ill at ease. To one side of him stood a tall middle-aged man whom he introduced as Alois Hersli, the Swiss federal official in overall charge of security at Davos.

The Doc spoke at the lectern from notes. Swiss army psychological experts had drummed his talking points into him during the night and he was not going to depart from them an inch.

"These are troubling times", he began. The room was transfixed, not by what he said, but by the way that he said it. This was not The Doc they were used to. All the affect had gone from voice and his body-language. There was no twinkle in his eye. He was not even looking up. He was, in fact, under instructions from the army experts not to "connect emotionally" with his audience at all, and he was embracing that ambition fervently.

"As you probably all know by now, yesterday evening two of our guests — our colleagues, our friends, I should probably say — were shot dead by unknown hands at around seven o'clock, while many of us were sitting down to dinner in this very building. I offer my deepest condolences to their families, as, I am sure, do we all." He paused for a few seconds to allow for a sympathetic murmur.

"After these tragic events, the Graubünden canton police force, in conjunction with the Swiss federal authorities, decided to close the valley with immediate effect, for a limited period, the better to proceed with their investigation, and, hopefully, to apprehend as rapidly as possible the perpetrators of these abominable crimes.

"The police, the army, and the federal authorities have made this decision. We must respect it and allow them to do their work. I fear that it may be inappropriate, and perhaps the police will consider it impossible, for The Circle to continue with its planned programme, so we shall not be holding any sessions today, and we shall update you via LiveRadius as to tomorrow.

"I regret the tremendous inconvenience this causes to all of you. On behalf of The Circle, and I know that the authorities feel similarly, I beg for your patience and understanding. As always, we are your service. Our director of communications — he nodded to Sandra Smiley — is here to answer any questions that you may have, but first Mr Hersli will say a few words."

The Doc stood back. Once Hersli was at the lectern, The Doc disappeared from view, to a chair made ready for him behind the stage.

He had been up all night with the army and he still had no complete picture of what was going on out there. Why him? Why The Circle?

And where was Philip? If only Philip were here, Philip would deal with all these people and brief him on what needed to be done. The absence of his chief of staff tormented him in some ways more than last night's assassinations; the latter were, to him, relative abstractions, even though he had known both victims. Assassinations were things that did not belong in The Doc's universe. Philip did.

Alois Hersli spoke in accented but effective English. He noted first the death of Alain Girard, then the helicopter crash, and only then the shootings. He said that each event was being thoroughly investigated by the Swiss authorities with assistance from appropriate services overseas where this was indicated.

He remarked that the shootings were probably not, as he put it, "amateur crimes". Beyond that, he could not speculate. The killers would be found and their motives established. The Swiss government was deploying a wide range of resources. In past years this might have been called a "manhunt". He apologised in particular that it had proved necessary to close the valley, but he hoped that everybody would bear with him until the police were confident that the valley could be opened again. He could not say when this might be expected. He raised his head from the lectern, thanked his audience for its patience, and stepped back.

His remarks were received with a polite silence, which gave way to a murmuring, which grew into an outcry. "You cannot keep us here", shouted one voice. "We demand a proper explanation", shouted another. Several people were booing loudly. A few were standing. "Where's The Doc" someone cried.

Sandra drew a deep breath and made her way to the lectern. The room quieted again. She introduced herself as The Circle's Director of Communications — "So communicate!", shouted someone at the back — and, in the circumstances, it was her pleasure, or rather her duty, to answer questions relating to the "ongoing situation", as she put it. Probably, she said, she knew no more than they did. Doubtless they were all following social media as well as mainstream media. She would be happy to confirm what The Circle believed to be facts — as opposed to speculation, in which they would not wish her to indulge. They were "all in this together", she said with a cautious smile. Note-takers, as in regular Circle plenary meetings, would capture keywords and phrases voiced in the room, and input them to a word cloud on the screen behind her. She looked out at the room. Chaos ensued.

The Aspiring Leaders and the temporary staff did their best, but nobody who got a microphone wanted to give it back. Soon sections of the room were almost fighting for possession, while everybody seemed to be shouting questions or insults without waiting to be noticed from the lectern. It looked to Sandra like the cast of Succession re-enacting Lord Of The Flies.

Markus Bern's security people were communicating feverishly on their earpieces, and were able to report that nobody was getting visible assaulted.

Individual voices broke through the cacophony. Was it true that all these crimes were related to the visit of President Zelenskyy? Would Zelenskyy still come? Was it true that Circle staffers had been taken hostage?

The note-takers were struggling to catch as much as they could, and the screen behind Sandra was filling with phrases and keywords. It was probably an error to be projecting them in bright red, as this made them look even angrier:

— "When did you know?"

— "Is Zelenskyy coming?"

— "Was the pilot on drugs?"

— "When can we go?"

— "Where is Middlewait?"

— "Is it the Russians?"

— "When can we go?"

— "You cannot treat us like this"

— "You are responsible"

— "When can we go?"

As the outbursts continued, four words gradually emerged in massive point-sizes to dominate the word cloud. They were "Go", "Know", "Sue", and "Zelenskyy".

The room was on fire. She could see a New York Times correspondent, who had a White Badge, talking into two phones at once. The next person was doing the same. Every phone and tablet in the room — probably averaging three per person — was pinging with social media notifications. Sandra took several deep breaths. It was not about her, she reminded herself. She was a well-paid lightning rod. Improvise but do not invent.

She called into her microphone for silence. When she called for the fourth or fifth time, the brouhaha subsided, and she began to speak:

"Let me address the question regarding the duration of the lockdown, which is obviously a matter of immediate concern ..."

She had not even finished that first sentence when a man in his fifties stood up at the front of the hall with a microphone in his hand and interrupted her. She recognised him as the foreign minister of one of the newer BRICS countries, so she let him speak.

"Is it true", he demanded, "that the US Secretary of State has already left Davos, together with all US Congressmen attending this annual meeting?"

All except for one Congressman, thought Sandra. They had indeed.

In a major error of judgment, Markus had revealed this piece of unbelievably sensitive information during an early-morning meeting attended by the managing board of The Circle. At about 4am the eight surviving American government VIPs had left for Zurich in two bullet-proofed, road-bomb-resistant minivans which the Swiss Federal Intelligence Service kept on hand for moments like this.

Sandra hesitated fatally. She could not deny the facts and she did not wish to confirm them. Her face flushed. Her mouth was dry. In the second or two that it took her to formulate an answer — she was minded to say that The Circle had made no such arrangements, which was true — her interruptor turned to looked at the room while waving a clenched fist. He began to shout, with a practised rhythm and an emphasis on the first syllable of the word:

"Disgrace! Disgrace! Disgrace!"

Then he jumped up on the stage, and continued in full flow:

"Shame on The Circle! Shame on The Circle! Shame on The Circle! One rule for Americans, one rule for everyone else, and no rules at all for the Americans who make the rules.

"Many of you here are Americans. Is it right that your officials go free while you are imprisoned? Is this what American democracy means? What will you say when the Swiss let you go free because you have American passports, and they keep the rest of us here, we people who don't have American or European Union passports, because they haven't found their shooter and we look more like their idea of terrorists?

"Is this what The Circle means by diversity? That we are welcome to decorate their oh-so-inclusive panels and plenary sessions, but not free to go home afterwards? That our White Badges are not quite white?"

He seemed to have the sympathy of the room, even getting applause for that last phrase, which was no small achievement given that the room was filled in large part with Americans and Europeans who had probably last applauded language like this when they were in college.

He was playing them and they were playing him. Nobody in the room wanted to be cooped up indefinitely, and if a muscular show of political correctness led by this accidental fireball was the fastest way of getting them out, then give it a go. Besides, they were pissed off, especially the Americans, about the Americans.

"Follow me to the Promenade", cried the newly endorsed Pied Piper. "We shall walk our way out of Davos. We shall assert our rights as citizens to move about freely and peaceably. We are not intimidated by the police, nor by the police state so genially represented here by Herr Hersli. We have no need of paternalism under the guise of protection. What is right for American officials is right for American citizens, and what is right for American citizens is right for citizens of all countries. Is that not so?"

He had reached his peroration.

"We demand that The Circle apologise to us all for its moral cowardice, for its double standards, and for its readiness to conspire with American and Swiss governments to imprison its own guests. The Circle says it does not know why we are detained here. Why then does it detain us? Let us all leave Davos together. We meet on the Promenade in one hour."

The Doc watched all of this on a monitor behind the stage. The terrible thing was, if you stripped away the more contentious phrasing, this was not very far from the truth. They had thought it the most natural thing in the world that Americans alone should be spirited away. The Circle was now the creature of the Swiss police. The Doc had invited three thousand people to Davos to change the world when his own authority stopped at the walls of the Congress Centre.

He recognised effective rhetoric, and he gave the foreign minister high marks. The minister had said just enough that was factually correct, and had leveraged that minimum viable truthiness into a specious justification for what he knew his audience wanted to hear, and, ultimately, what the minister himself presumably wanted to achieve, namely, the condemnation of The Circle in the name of its own members.

Half of The Doc was appalled, half of him was fascinated. If he had his life over again, The Doc thought, he would want to be standing where that man was standing. That was where the real argument was.

As it was, he had appointed himself Admiral of a fleet that was now sailing away without him, before his very eyes, towards a New World disorder in which power would belong to a violent cabal of disparate countries bound to one another only by their common hatred for the remnants of the old order which The Doc had devoted his life to nurturing, and which he had imagined to be eternal; an order which was "not an ideology", as he liked to say, "but an equilibrium".

But The Doc was not The Doc because he gave in easily, nor because he lacked adaptive instincts. Listening to the foreign minister, he could almost feel own his certainties shifting. As he liked to remind The Circle each year in his opening remarks, he was at heart a principled pragmatist, a realist who believed in the reality of ideals, an optimist of the will — and now this turmoil was speaking to the pragmatist in him. It was telling him something. In a sense, it was happening in order to tell him something.

How in this week's opening sessions had he neglected to single out and charm this foreign minister who was now emerging as his nemesis? Why had nobody flagged the name for him? Obviously this man ought to be his objective ally. He was only stirring discord now in order to demand The Doc's attention, to win The Doc's respect.

The world was changing. The Circle had to change. Structurally. Seriously. Not superficially, as before. It was not the method that was wrong but the mix. The Circle needed less America, roughly the same amount of a wider Europe, more BRICS even if they kept on interrupting. Let new people push in new directions. Listen to them. Learn from them. Steady them as they go.

The Doc halted his reflections for a moment. He was overturning his convictions of half a century in the space of half a minute. Was he going mad?

At that same moment the foreign minister jumped down the stage and gestured to the audience to follow him.

The plenary room in the Congress Centre had seen many standing ovations, but none quite like this one. The crowd rose to its feet applauding. Then it surged towards the exits. If the Congress Centre had been a football stadium, the stampede might have killed dozens. As it was, there were enough doors. The crowd solved for equilibrium by adjusting their demeanour to that of opera-goers leaving Lincoln Center.

Olena had been standing at the back of room behind the last row of chairs. She was not among those rushing to leave, since she was hoping to spot Karl, and she had resigned herself to being jostled by the throng. Then she noticed that the man in the chair just in front of her, who had stood up to leave, seemed to be swaying. A lot. He was clutching at the chair in front. He was trying not to fall over.

She heard him speak: "Can someone help me please? I feel very dizzy …"

She recognised him. It was Mark Massover, the CEO of Carbon Markets Integrity. He had been pinging her for a meeting since Sunday.

"What's the problem?", asked Massover's departing neighbour to the left, who turned back when Massover spoke.

"I have to confess", said Massover, now in desperately weak tones, "that I don't feel at all well. I fear I may pass out. Could you possibly call a doctor?"

If Massover seriously expected anybody to find him a doctor in this hubbub, thought Olena, he was definitely in a bad way. Subsequent events confirmed her diagnosis. Massover collapsed sideways and his head hit the carpeted concrete floor with a thump that even Olena could hear.

To be continued tomorrow ...